Don't Forget the Customers!

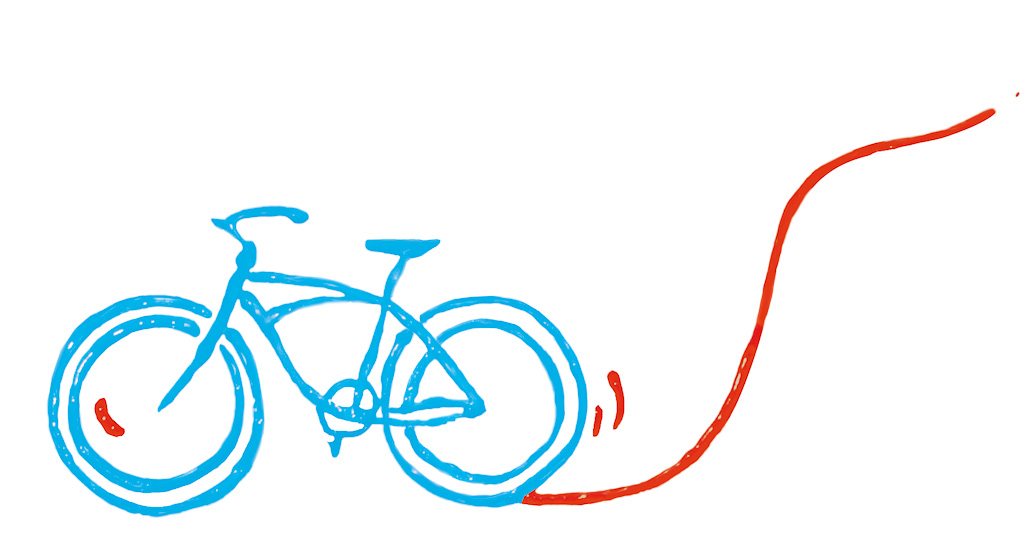

In 2004, Japanese bicycle parts maker Shimano explored creating a new bike to grow its market share, which had reached a plateau in high-end road-racing and mountain bikes.

Instead of calling in end-stage bike designers, Shimano invited design firm IDEO to collaborate right from the start of the process.

The IDEO-Shimano team – engineers, designers, behavioural scientists, marketers – spent a lot of time trying to understand cyclists and non-cyclists. The average American, they found, felt intimidated in a high-end bike store; they were daunted by complexity, cost, even specialised clothing.

Human-centred exploration helped Shimano realise the large untapped market for casual bikes that bring back childhood cycling memories. The result? The “coasting” bike – no controls on handlebars, no cables, brakes applied by backpedalling – now made by at least 10 manufacturers.

This example, highlighted by IDEO President Tim Brown in a June 2008 Harvard Business Review article, Design Thinking, was the result of an innovation process that placed the user right at the centre.

Call it what you want – IDEO’s founder David Kelley decided to call it “design thinking” in 2003 – but this way of designing products and services based on users’ perspectives is catching on globally.

With its rising profile and reported benefits – not just in product design – but also in redesigning service experience and even social assistance programmes in rural villages, public agencies here have also begun to test out the design thinking approach.

Feel the “Customer Journey”

The Manpower Ministry (MOM) is among the early adopters. In 2009, its Work Pass Division collaborated with IDEO to redesign its Employment Pass Services Centre, as part of its business process redesign cycle.

As Dr June Gwee notes in Redesigning the Service Experience (Ethos Issue 8, Aug 2010), instead of looking at employment pass services as a series of functional processes, the division began to consider them through the eyes of users – employers, employment agencies and foreign workers.

“The Work Pass application transaction was recast as an experience (emphasis added) – applicants were not units to be moved from point to point in the process but instead were individuals with aspirations, preferences and relationships,” she writes.

The redesign required officers to better understand opportunities and difficulties facing users who had succeeded or failed in using the existing process, encountered problems or just avoided the whole process.

Officers used field observation to understand the “customer journey”. Instead of relying on floor plans for renovation, MOM officers made a prototype of the Centre’s layout by using foam boards, props and lightweight furniture. They also role-played as customers to finalise ideas, making changes such as lowering the finger-printing machine to a more comfortable level.

The project that spanned five months created a much more welcoming space. Among the changes: roaming customer service staff; waiting areas with views of the skyline; users addressed by name and not numbers; families served in cheerful cabanas while children are occupied with toys.

More significantly, officers learnt that users wanted certainty in their applications, and this led to an appointment based service. It boosted productivity greatly: users are now served within 15 minutes, with 90% under 10 minutes– down from a dreary four-hour wait in 2002. The centre, which serves up to 900 daily, scored 5.5 out of 6 in user satisfaction.

Tim Brown told Challenge that the redesigned experience goes beyond boosting efficiency. “By thinking about how we deliver the emotional and functional needs of our customers...we can make a difference to how it feels to be a citizen of a place, we can make a difference to how it feels to be a Singaporean and how it feels to be in Singapore.” (emphasis added)

This ‘feel-good’ factor which makes a country more attractive could even give it an edge in attracting talent in this highly competitive world, he adds.

New Tools that Add Value

Mr Brown notes that many of the most successful brands create breakthrough ideas inspired by a deep understanding of customers’ lives and use the principles of design to innovate and build value.

In their quest to match human needs with available technical resources within practical economic limits of business, designers have honed skills to create enjoyable products, he says in his book Change by Design.

And design thinking goes one step further: “[It] puts these tools into the hands of people who may never have thought of themselves as designers and applies them to a vastly greater range of problems.”

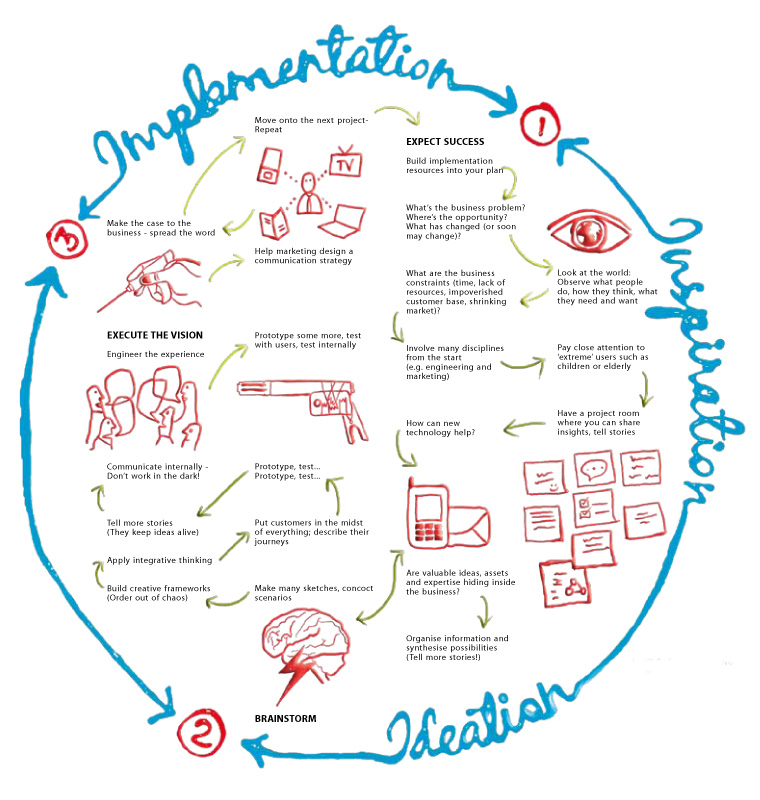

So design thinkers use creative thinking tools and skills like observation, brainstorming and experimentation to derive possible solutions, while bearing in mind the “customer journey”.

Design thinkers go through a “system of spaces” that overlap fluidly between inspiration, ideation and implementation. (See diagram above) Mr Brown warns first-time design thinkers that the approach may feel ‘chaotic’ as the three stages are meant to be fluid, not structured.

A design thinking team comprises people from various specialisations, emphasising collaboration across disciplines so that more innovative alternatives can come from a broader worldview – something like the Public Service’s “whole-of-government” interagency approach.

One point to note is that the classical sense of design and design thinking are not the same, yet they are intertwined. Mr Brown observes that, historically, designers were called in at the last stage of the innovation process to “put a beautiful wrapper around the idea”.

Design thinking is about involving designers right from the start – this is more strategic and creates new forms of value by giving a tool for imagining what will satisfy users emotionally and giving these experiences a desirable form.

“The notion of design has come back into the ‘business conversation’ in full force in recent years because there are a number of economic, social, environmental and political challenges that more linear and analytical approach have been unable to solve,” says Ms Heather Fraser, Director of Design Works, a Rotman School of Management’s centre for design-based innovation and education.

Rotman has collaborated with Singapore Polytechnic to set up DesignWorks Singapore to promote design thinking in enterprises here.

She adds, “Suppressing human creativity and discounting intuition as a source of inspiration and innovation... hold us back from breakthroughs.”

Design thinking is set up as the creative, intuitive approach to balance out (not oppose or replace) the ‘analytical’ approach favoured by organisations.

“Nobody wants to run a business based on feeling, intuition and inspiration,” admits Mr Brown, “but an over-reliance on the rational and analytical can be just as dangerous.”

The “Experience Economy”

Design thinkers would be first to admit that what they do is not new-fangled; being human-centred is age-old. “It may be common sense, but surprisingly, not common practice,” says Ms Fraser of DesignWorks.

Despite how ‘natural’ it seems to consider users’ needs and worldviews, the pressure to stay ahead of competitors has forced many organisations to focus more on optimising current systems instead of also tapping intuitive, empathetic approaches to opportunities and innovations.

But consumers are much more sophisticated today, so businesses have to dig deeper to identify still unsatisfied needs, she adds.

This has been dubbed the “experience economy”, where consumers increasingly seek satisfying and delightful experiences – be it the pleasurable unboxing of a well-designed product to the (irksome) filing of taxes (how do we make it more painless?).

quips Mark Wee of UNION, an experience design studio that worked with the National Library Board (NLB) to form STUDIO, an initiative that helps organisations innovate user experiences using design thinking.

PS21: Ready to Explore

The PS21 Office is eager to explore how it can “reap fresh insights into policies and processes,” says its Director, Agnes Kwek.

She acknowledges that agencies have been successful with time-tested methods to formulate policies and programmes, such as using research data and studying best practices. But sometimes, what is missing is an intimate understanding of the needs of the customers, from their point of view.

“We sometimes neglect the important facet of ‘user acceptance’ of the solutions we create,” she says. “The best solutions are ineffective unless our customers, the public, have a high rate of acceptance and adoption. And to do this, we must first put ourselves in their shoes.”

Ms Kwek admits that design thinking is “new ground” and “it is too early to tell to what extent it will work in the area of public policies. However, in the spirit of experimentation and ‘safe-fail’, it is worth a shot.”

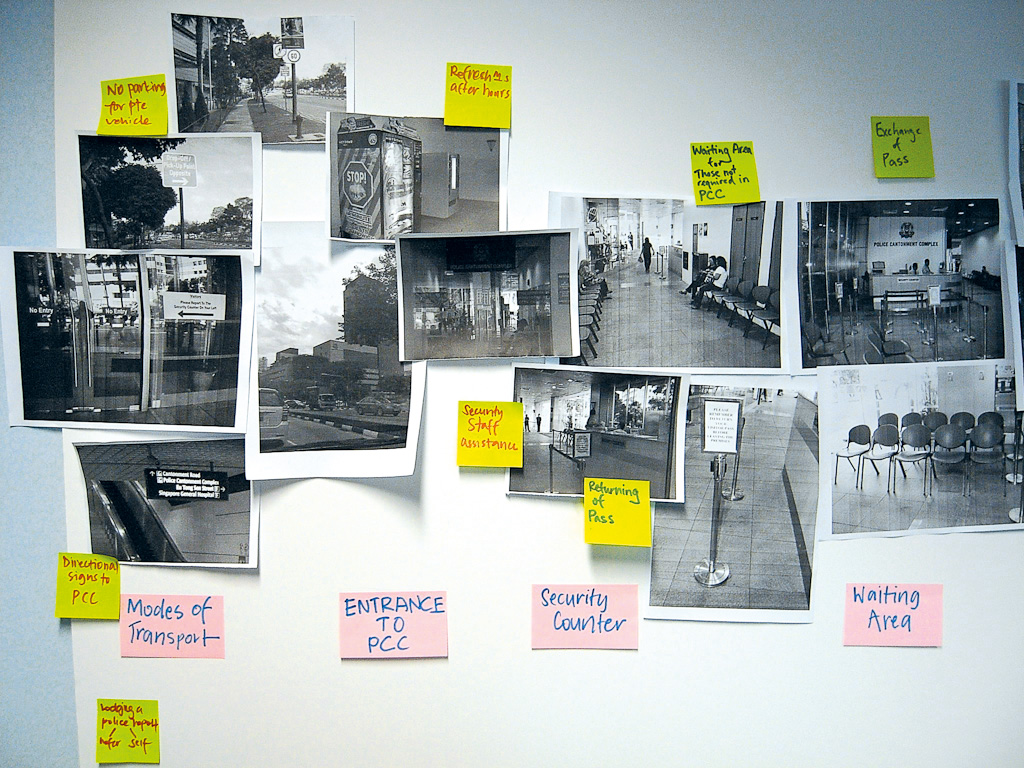

The Singapore Police Force has also made a foray into design thinking. In 2009, it worked with STUDIO on a trial project to look at the problems counter service officers at neighbourhood police centres face daily.

Police officers who participated are tasked to infuse design thinking into existing work improvement initiatives like Staff Suggestion Schemes and Innovation Teams.

“We interviewed both the officers and the public. We gathered plenty of research data through video recordings and analysis. One unique aspect was the use of ‘body storming’, which meant officers [physically] simulated the environments and conducted lots of role-playing to understand the needs of both officers and the public,” explains Assistant Commissioner (AC) Lau Peet Meng, who initiated the project when he was Commander of Central Police Division.

He had attended a six-month design thinking course conducted by the Stanford Business School and the Stanford Institute of Design.

What stands out about design thinking for STUDIO members is its “extremely visual nature”: graphics, videos and photos were used to help them understand problems faced by the public when lodging police reports; mock counters were set up and police officers role-playing users and counter service officers could put themselves in the shoes of both parties. They also carried out rapid prototyping using paper to create a mock Online Reporting Kiosk.

“Traditional problem-solving approaches start with a ‘problem’ and then try to solve it – sometimes even when the problem is poorly defined! Design thinking starts with a ‘user’ and asks what ‘needs’ he has that can be better met, not what needs we think he has,” adds AC Lau. “It emphasises rapid prototyping and testing ideas in real situations.”

In her article, Dr June Gwee points out that design thinking has yet to become widespread in the public sector as it “may appear irrational, abstract or even extravagant with outcomes that may not be directly measurable or tangible” which is at odds with how public spending is traditionally accounted for.

Design is also often regarded, at best, as a “good-to-have element of other key public roles instead of being itself a strategic function of operational planning”, she observes. “Most public agencies are the sole providers of unique and often mandated services; there is inherently no strong impetus to radically reinvent their services and operations, and little comparative basis with which to make changes.”

A New Key Ingredient

Indeed, agencies seem to be taking a cautious approach before jumping onto the design thinking bandwagon. Challenge understands that a few are exploring but declined to reveal more. There also seems to be a notion that design thinking is ‘costly’.

But this is likely to change now, with the government making a concerted effort to push for design thinking.

At the President’s Design Award ceremony in November 2010, Minister for Information, Communications and the Arts Lui Tuck Yew said the government has identified design thinking as “one important ingredient” to drive Singapore’s ability to create original and differentiated products and services that the global market demands.

He revealed that more than 2,000 people from the public and private sectors have attended design thinking workshops and seminars organised by the DesignSingapore Council and its partners. The council is also engaging senior and middle management to see how design can be strategically adopted to drive their organisations’ outcomes.

As a sign of commitment, the council is investing $7.5 million to establish the Design Thinking and Innovation Academy to introduce programmes to build design thinking capabilities.

For agencies keen to adopt the methodology, Dr Gwee outlines three success factors: mindset, methodology, and organisational culture and competency.

Organisations need a mindset that appreciates design thinking principles: the capacity to experiment, take risks and explore radical possibilities.

For agencies new to design thinking, she recommends that they appoint consultants to transfer knowledge of the methodology, bringing officers through the paces in actual projects to learn on the job.

Design thinking must also be imbued in the organisation’s long- and short-term planning: both management and staff apply it from product and service development to planning, communications and service delivery.

“The only way to ‘cultivate’ a design thinking culture is to allow more people to get their hands ‘dirty’ working through an actual project. So time and appropriate training will be the key obstacles.”

While design thinking has admirers, it has detractors too. The criticisms are wide-ranging: some say design thinking has succumbed to business realities where great product ideas are watered down because risk-averse businesses believe they can’t sell enough to justify the product’s existence; others say design thinking’s methodical process is itself a paradox, despite Tim Brown stressing that the process is not sequential but fluid.

As Brian Ling of design firm Design Sojourn says on his blog, “dictating design thinking as a sequential step-by-step process is ripe for failure in the creativity and solutions department. This is probably why after half a decade, the companies that are creating innovative products continue to be the usual suspects... Therefore I feel design thinking has not produced the results the business has been hoping for, and despite the best efforts, design thinking will continue to be something only a few can do well.”

No Magic Bullet

Other critics say design thinking has joined the slew of ‘creative methods’ as a nicely packaged product taught in schools and touted to be the next big business trend when, in fact, it should only be seen as part of a larger toolbox for business creativity.

But design thinkers say they never touted a panacea. Stressing the integrative nature of design thinking, Ms Fraser says: “Success is a matter of many factors – creative opportunity-seeking, solution development along with deep technical skills, analytical rigour, management leadership and acumen, and other vital skills.”

Mr Wee of UNION adds: “It’s about being able to provide space where people can test out a number of solutions before we can confirm one, and learning from other disciplines, using their examples to see how they can address our issues. It’s an approach that’s very logical.”

Design thinking also does not promise overnight change. AC Lau says: “I wish I could say we fundamentally changed the way we did counter service in the Police – we didn’t. But we raised important questions and made some interesting experiments that continue to shape the way the Police sees counter service, for example, should officers at counters also handle phone calls? We had found this to be a major drag from the user’s perspective.”

He adds: “Design thinking is a really powerful tool. I am hopeful this will mean that the Public Service will, as a result, be better able to deliver the kind of service Singaporeans deserve this side of the 21st century”.

- POSTED ON

Jan 18, 2011

- TEXT BY

Chen Jing Ting

Bridgette See

-

Deep Dive

Strengthening Singapore’s Food Security

-

Big Idea

Why Facts Don't Change Minds