Rental Support During COVID-19: A Lifeline For SMEs

Take a global pandemic, compound it with a nationwide lockdown and what you get is a massive blow to any small and medium enterprise (SME). This impact is not limited to SMEs, but has a substantial knock-on effect on the whole economic ecosystem.

SMEs play a critical role supporting in the Singapore economy, employing almost 72% of our workforce, says Kiron Cheong, Senior Assistant Director of Civil & Legislative Policy Division at MinLaw. “If many SMEs did not survive (during the Circuit Breaker), the domino effect on the rest of the economy would have been substantial.”

Recognising this long-term symbiotic relationship of both tenants and landlords, MinLaw proactively moved to develop two new legislative frameworks to help SMEs cope with rent, a significant part of their business costs, to better weather the impact of restrictions.

The 2020 Rental Relief Framework and the subsequent 2021 Rental Waiver Framework were devised to establish, through the provision of rental waivers, the co-sharing of rental obligations between the government, landlords and tenants.

According to Cheoh Wee Keat, who was then the Deputy Director of Land Policy, MinLaw, some landlords proactively provided rental assistance to their tenants, but others did not. It was thus important to have frameworks that would “intervene specifically and substantively” in the area of rental obligations.

Covering All Bases

When work started early in the pandemic in 2020, there was no local precedent. The team had to develop frameworks that were unique for the circumstances. Beyond reliefs, eligibility and the obligations, they had to consider many other factors.

“It was definitely a stressful time,” Wee Keat recalls. “Countless nights were spent agonising over whether we had covered the huge variation of circumstances such as the types of leases, the relationships between the landlords and tenants in different types of properties.”

The team considered numerous variations and definitions – even basic ones such as what constituted an SME. “It was important for the underlying laws to be as clear as possible to minimise legal disputes later on,” he shares. “There was a worry that we may not have gotten everything right given the time pressure and the constantly evolving situation.”

What heartened the team was how other Public Service agencies, senior management and the political office holders also worked tirelessly with them to collectively push out the framework, to ensure that the impact on SMEs was alleviated in a timely fashion.

Another big challenge was finding convergence. “At first glance, the interests of the parties appear to be entirely divergent – tenants would naturally wish to obtain the maximum amount of relief given the impact of COVID-19, while landlords would want to continue to receive income from their properties as they may also have their own commitments in the form of mortgage payments,” Wee Keat says.

Yet it was also in the interest of landlords to prevent their SME tenants from winding up as replacement tenants would be hard to come by. The value of a property devoid of tenants would then fall, cascading into much broader repercussions on the economy.

Accepting a Little Discomfort

The legislation recognised these mutual circumstances and aimed to strike an appropriate balance, Kiron explains. In coming up with the framework, they looked at other countries’ measures; some countries went with a blanket moratorium on landlord action for commercial rent arrears, while others deferred repayment of rental arrears by almost two years. While these measures may have brought some respite, the financial burden remained.

In Singapore, the approach taken was to co-share the costs of rent between the government, landlords and tenants. “In some ways, by taking a short-term ‘pain’ of mandating the co-sharing of the rental obligations for the Circuit Breaker and Phase 1 periods and [later] the Heightened Alert periods, we were in fact giving better long-term certainty to both tenants and landlords,” Kiron says.

Some flexibility – such as scoping the frameworks to apply only to SMEs significantly impacted by COVID-19, as well as leaving room for landlords with extenuating circumstances to seek an assessment to reduce their obligations – meant a lot more work for the team, but more importantly, also meant that help could be more appropriately and fairly given.

“We knew that fixing these parameters could be criticised as arbitrary, and there would be some hard cases, but we also knew that the line had to be drawn somewhere,” Kiron reflects. “As you can imagine, the legal and policy teams had to work extremely closely to consider both landlords’ and tenants’ interests holistically, and at the core of it all, to ensure as far as possible, that the frameworks were fair.”

Getting Down on the Ground

This ethos of looking out for SMEs was extended to meet ground-level considerations. MinLaw engaged over 500 private sector stakeholders for the Rental Relief Framework in 2020 and Rental Waiver Framework in 2021 across six sessions. These engagements provided valuable insights that informed the final policy and implementation parameters.

Kiron recalled some landlords sharing at one Rental Waiver Framework feedback session, that they had voluntarily provided support to their tenants even before the Phase 2 (Heightened Alert) periods.

“These landlords were concerned that they would be ‘over-penalised’ if the Framework did not take into account the prior goodwill assistance they provided to tenants,” Kiron says. “We studied this feedback carefully and discussed the same with other stakeholders, and decided that if such goodwill assistance had previously been rendered, they should be taken into consideration, but on a case-by-case basis.” They were given the option to seek an assessment on whether it was “just and equitable” for them to have their obligations reduced or reversed.

Such cases came under the purview of Minlaw’s Rental Waiver Registry team, which was charged with supporting a group of independent assessors, liaising with landlords and tenants, obtaining information needed for the assessments, and ensuring that assessments were expedient.

According to Annie Ang, Deputy Registrar from the Rental Waiver Registry team, one landlord sought an assessment because they had proactively offered a 55% reduction in rent to a tenant for a short-term lease extension. Both parties were informed that the Framework allowed for rental or direct monetary assistance provided during specific periods to be offset from the rental waiver obligations, Annie says. “With the information, they reached an amicable agreement privately.”

In another case, a landlord had suffered a recent heart attack, an unforeseeable circumstance that had to be considered, as this affected his ability to work and caused him financial stress. “The rental from the property was his only source of income,” Annie says.

“While he technically did not qualify under the objective criteria for an exemption, the team helped to gather the necessary evidence from the landlord about his ailment, to give a factual representation to the assessors.” The assessors granted his case under special considerations, and exempted him from the rental waiver.

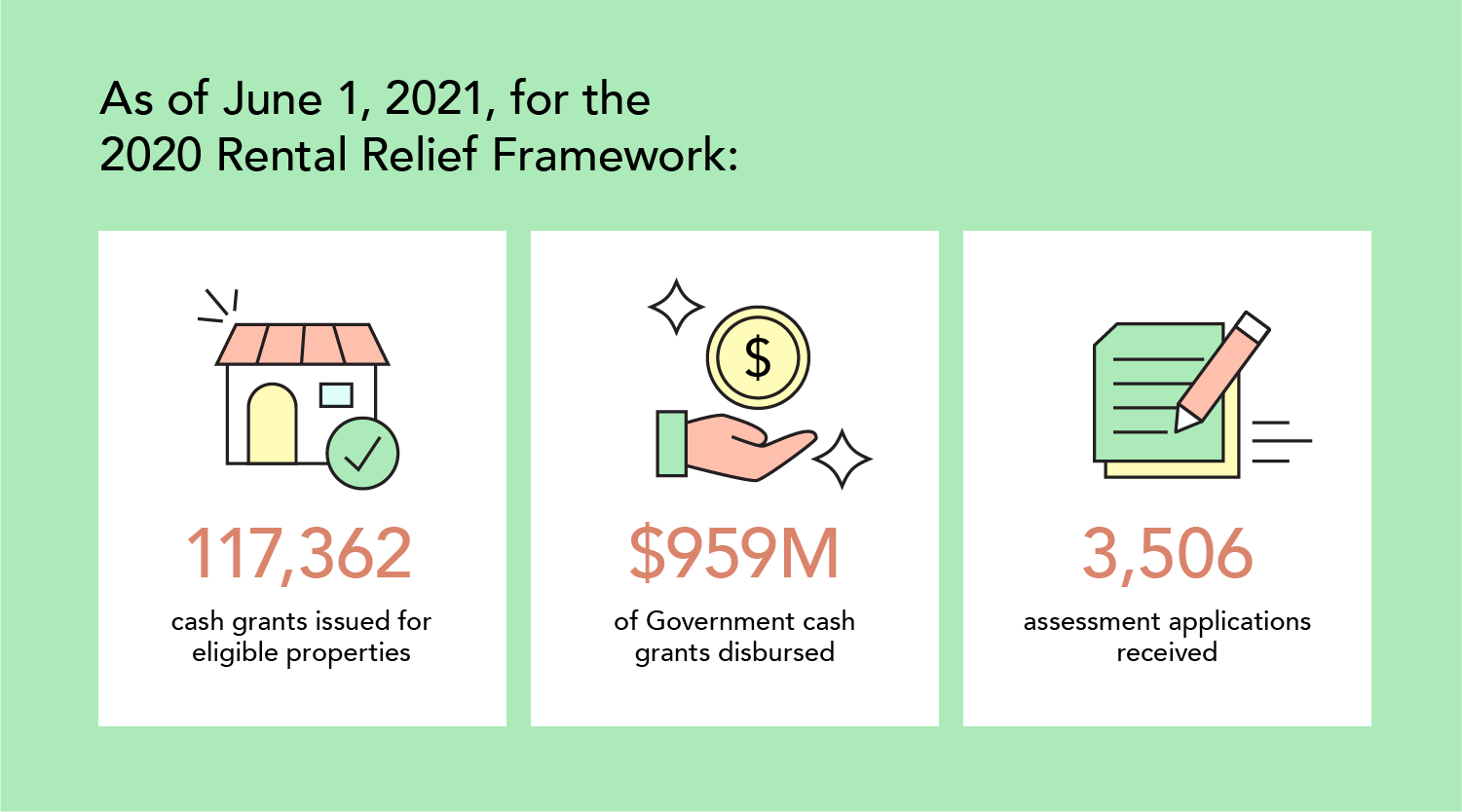

All in, about 260,000 SMEs have benefited. Of these, an estimated 31,000 were SMEs in retail and F&B. The latter, which was most severely affected, received Additional Rental Relief borne by landlords.

Serving Singapore as One

For the many officers involved in this support scheme, the experience has not only been rewarding, but career-affirming.

“It was an honour to be a part of the team developing, implementing, and operationalising both the Frameworks, which many SMEs likened to a ‘lifeline’ for them,” says Kiron. The experience has underscored in him a desire to “always seek improvement to serve the interests of Singapore and Singaporeans”.

It also highlighted that in times of adversity, public officers were willing to collectively pull together to address the unprecedented challenges that COVID-19 had introduced. This spirit of cooperation across all parts of the Public Service was extremely heartening, and kept them going, says Wee Keat.

“The past two years have really underlined the fact that the challenges that the Public Service encounters are becoming increasingly complex and multi-disciplinary. It is important for us to learn how to connect with the relevant colleagues and draw on each other’s strengths to solve today’s problems.”

- POSTED ON

Jul 6, 2022

- TEXT BY

Sheralyn Tay

- PHOTOS BY

Courtesy of MinLaw

- ILLUSTRATION BY

Lei Ng