Working With The Dead For A Living

The restaurant is buzzing with the dinner crowd when Dr Marian Wang’s mobile phone rings. It’s an investigation officer with the Singapore Police Force, but before he can say more, Dr Wang is ready. Reaching for the change of clothing she always carries with her when she is on call, she swaps her heels for a pair of sturdy shoes, and travels to where a dead body awaits.

Dr Wang, 37, is a forensic pathologist with the Health Sciences Authority (HSA). Forensic pathology focuses on studying the dead to determine the cause of death. This is the profession that inspired Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and later, the popular television dramas CSI and Bones.

“It’s really not like those shows at all,” says Dr Wang with a laugh. Except when causes are visible only in life, not death, such as arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) or electrolyte disorders (imbalances of salts in the blood), she can always determine the cause of death. “There’s no glamour or mystery.”

Maybe not, but still, hers is no ordinary workday. Dr Wang takes turns with five colleagues to be the forensic pathologist on call with the police. For one week, she participates in every crime scene investigation in Singapore involving suspicious deaths, at every hour of the day or night – and death, it seems, has a preference for night.

At the scene of death, Dr Wang might find herself in an HDB flat, tromping into the jungle, or peering down a drainpipe. After flashing her identification card to the uniformed officers, she gets down to work, snapping on a pair of gloves, and documenting her findings with a notebook and camera.

While the police investigators collect evidence from the surroundings, Dr Wang retrieves evidence on the body – swabbing for saliva and collecting hair strands in specimen bags. No two cases are alike and her specific approach will vary accordingly.

She determines the time of death, identifies the potential weapon responsible for inflicting injuries, if any, and helps to reconstruct the crime scene. The end result, which may come hours later, is preliminary information indicating the possible cause of death. Dr Wang then supervises the removal of the body and performs an autopsy. In the weeks following, she continues to work with the investigative team and the courts until the case is resolved.

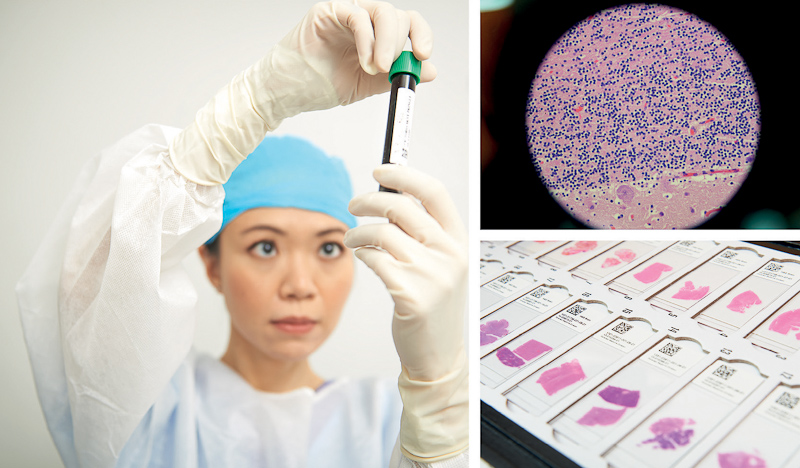

Right: Tissue samples are processed by lab technicians and put onto glass slides for examination under a microscope.

On the day-to-day

When Dr Wang is not on call, she is likely to be on morgue duty for non-suspicious cases: deaths of hospital patients, drug overdoses, suicides or accidents.

In the morgue, the atmosphere is serious and professional. “It’s like working in an operating theatre, minus the anaesthetist and the anaesthetic equipment,” Dr Wang says. “The nature of the work is serious, but we try to make it not excessively solemn.”

She wears surgical scrubs; her tools, similar to a surgeon’s, are at the ready. Working beside a forensic technical officer, she examines an average of four to 10 bodies daily for the cause of death.

A post-mortem examination starts with the exterior of the body. First, Dr Wang looks for distinguishing features such as scars or tattoos to confirm the person’s identity. Then she documents any external injuries or signs that suggest the cause of death, noting her observations on a body chart. Yellowed skin might suggest liver disease, for example, while bulges in the fingernails could indicate lung or heart conditions.

In some cases of natural death, there is no need for an autopsy – an external examination suffices. In other cases, where the cause of death is not obvious or when the death is classified as unnatural, a full autopsy must be done. After reviewing the circumstances of death and the deceased’s medical history, Dr Wang will recommend if an autopsy is needed and the Coroner (sees sidebox) will authorise the autopsy.

Bottom Left: Dr Wang makes incisions with a scalpel and holds skin back with forceps.

Right: In the morgue, Dr Wang uses a body chart to note her findings.

A deeper look

In a full autopsy, which can take from 1.5 hours to several hours, Dr Wang opens up the body to examine the internal organs for injuries or the effects of natural diseases. With a knife, she makes a Y-shaped incision from both sides of the neck, meeting at the breastbone and continuing down the middle of the torso. An incision is made to the scalp to remove the skullcap so she can examine the deceased’s brain. By then, her gloved hands will be messy, so she dictates her findings to her assistant to take notes.

More detailed examinations for complex homicides can take up to an entire day. For suspicious deaths, police photographers and investigators attend as well. If necessary, Dr Wang will take tissue, blood or urine samples to test for poisons or drugs. She may also run the body through a CT scan to check for fractures or weapon fragments that remain in the body. Investigations into cases like these can take weeks to wrap up.

Occasionally, Dr Wang discovers that a non-suspicious case is actually the result of foul play. In one recent case, an elderly woman seemingly died of natural causes. Upon close examination, however, Dr Wang discovered some bruises in the woman’s neck muscles, a fractured voicebox and petechial haemorrhages (small pin-point bleeding on the skin that result from pressure) in the linings of both eyelids, indicating strangulation. The police were called and the perpetrator was caught shortly thereafter.

Dr Wang’s work has contributed to workplace safety too. Once, an electrician was found unresponsive at the foot of a ladder with a laceration on the back of his head. Initially, it was believed that he had died due to a head injury after falling off the ladder. But an autopsy revealed that the cause of death was electrocution. With this knowledge, the relevant authorities immediately closed the worksite for further investigations.

When Dr Wang is not in the field or the morgue, her days are full with reporting and follow-up meetings with the police and public prosecutors. Complicated cases may require a solid week of round-the-clock work. Dr Wang also appears in court as an expert witness, and teaches undergraduates and police officers.

Pursuing a passion

Dr Wang has practised forensic pathology full-time with the HSA since 2007, and it is only getting more challenging. “As the field advances, so do the expectations of the police, lawyers and courts of law,” she says, and so must her skills and knowledge.

She first became interested in forensics during a surgical posting. At first, her friends and family were sceptical. “But what inspires me is teamwork,” says Dr Wang. “I work across a broad spectrum of disciplines: medicine, legal, law enforcement. I have my part to contribute to a death investigation.”

More than that, forensic pathology is leading to new discoveries in medicine, particularly in the area of infectious diseases. Forensic findings can also influence workplace and health policy decisions.

“Eventually,” she says with a light laugh, “my relatives got used to my work.”

So how does a person with such a sunny disposition work with the dead for a living? Dr Wang has a quick answer: “I have to take a clinical approach. I have to maintain [an emotional] distance from the body before me.” This is a practised skill developed over years of medical training.

But more to the point, she says: “I don’t see myself as working with the dead. I’m working for the living, helping them bring closure to the death of a loved one.” And then she pauses and for a moment her eyes darken. “But children are always a pain point.”

She adds: “When you see people die, especially at an early age, you realise that life is precious and unpredictable. I value my loved ones every day.” So then, it is in the most unlikely of places – death – that Dr Wang finds a keen sensitivity towards the fragility of life.

Know the terms

Pathologist: A medical examiner who studies the changes in tissues, cells and body fluids caused by disease and injury.

Forensic pathologist: A medical examiner who specialises in determining the cause of death by examining a corpse.

Coroner: A District Judge of State Courts who confirms and certifies a death.

- POSTED ON

Sep 1, 2014

- TEXT BY

Kate Lilienthal

- PHOTOS BY

Lumina

-

Profile

Marieta's Little Miracles