What Does It Take To Save A Wild Animal?

At 8 a.m. on a Monday morning, veterinarians at the National Parks Board’s (NParks) Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation already have patients lined up and waiting to be examined. Working through the day’s patient list of bats, snakes, birds, and civets, vets must now decide which animals need care more critically.

They start by checking the animals brought in the night before, assessing their condition and ensuring they are stable before tending to inpatient animals. The Centre functions like a hospital, tending to orphaned, injured, or sick animals.

This is the daily routine for the vets at the Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation, a veterinary care facility that rehabilitates animals for future release into the wild. When Challenge visited the Centre, we witnessed the tender care given to four animal patients, each highlighting a unique lesson and challenge that vets at NParks face.

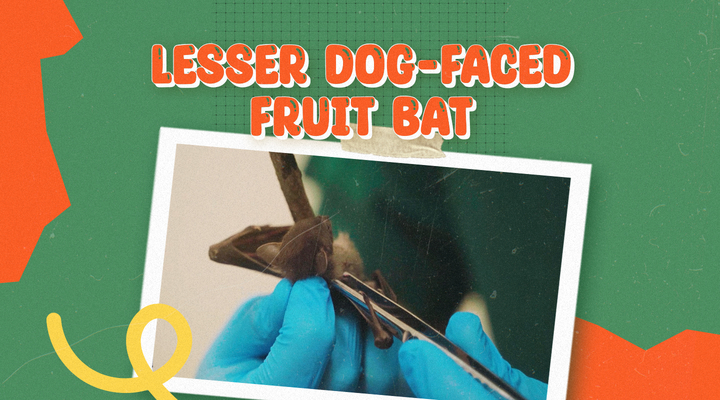

Patient 01: Lesser Dog-faced Fruit Bat

With a fruit bat in one hand and a tweezer in the other, a vet tenderly surveys the palm-sized creature for parasites. This bat was found orphaned beside its mother, who unfortunately passed, and NParks took it in to give it another chance at life in the wild.

This simple examination is just one of the many duties that NParks vets have to take on. Aside from conducting routine health checks and observations, they also perform surgeries and, when needed, collect fruits, leaves, and insects to provide a naturalistic diet for the animals. The main goal here is to rehabilitate, not domesticate. Instead of housing animals, they help them regain the ability to fend for themselves before releasing them back into the wild.

But picking out parasitic flies on a single bat seems to be a simple and redundant task, which begs the question: why not let nature take its course? Why intervene? A vet explained that caring for these animals is a duty they have as a country that lives amidst nature.

However, their duty goes beyond their role as veterinary medicine practitioners. They are also responsible for maintaining the operations at the Centre, performing “behind-the-scenes” tasks such as staffing, procurement, and even finance—to a certain degree. It’s almost like doctors running an entire hospital.

Beyond rehabilitating animal patients and running the Centre, NParks vets also participate in external stakeholder events. From organising hands-on sessions for youth at World Wildlife Day to engaging with pet owners at events like PetExpo and Pets’ Day Out, the vets are provided with opportunities to build on their managerial skills and soft skills.

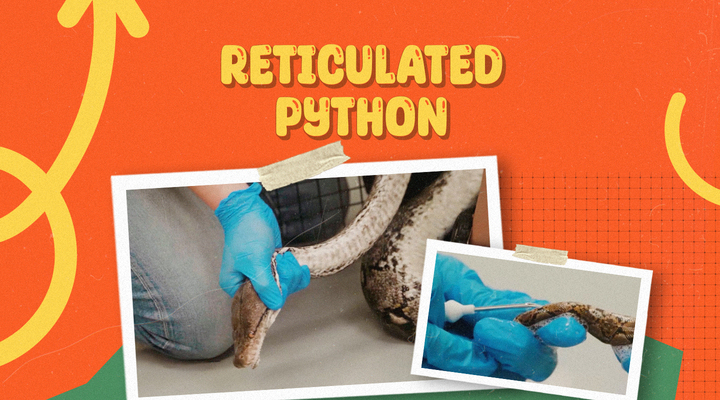

Patient 02: Reticulated Python

While the fruit bat is generally tame, you might wonder how vets handle more “dangerous” animals, such as pythons.

As people often panic when they see a snake in their vicinity and may hurt it unintentionally, vets first pay attention to any abnormalities in its body, especially its mouth and head, as these areas are more prone to injuries. If the snake requires additional care, the team will provide it; otherwise, the snake will be prepared for release back into the wild in a suitable area away from human activity.

For reticulated pythons, the vets also microchip them before they are released into the wild. Each microchip has a unique code that allows the Centre to identify the animal if it is recaptured. If they are brought to the Centre again, vets can refer to previous data when devising a treatment plan, or consider alternative areas for release.

As the vet sanitises a python's tail and injects a microchip into it, he tells us that snakes are misunderstood creatures. For pythons, their first instinct when encountering people is to move away instead of attacking. “They are generally quite chill,” he added.

Despite this, he never lets his guard down when handling them, especially when they are smaller in size. “From my experience, it’s the tiny ones that will bite you,” he said with a chuckle.

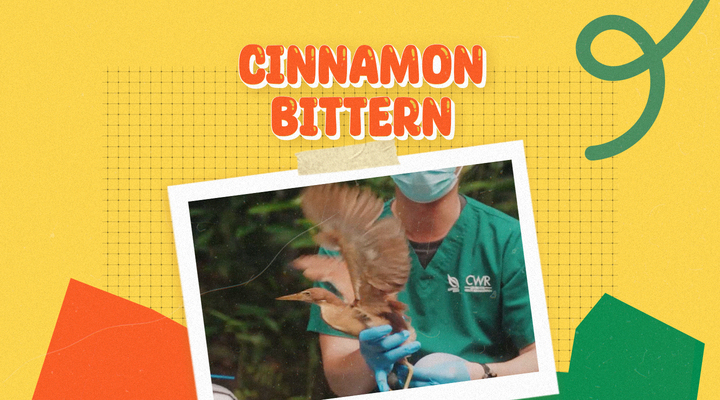

Patient 03: Cinnamon Bittern

The next patient is a Cinnamon Bittern that has almost fully recovered, and after vets are done testing its ability to stand and fly, it will be ready for release. Since the Bittern came into the Centre, the yellow bird gradually regained strength in its legs after two weeks of rehabilitation, from being unable to stand to being able to walk around on its two feet.

However, not every animal recovers this quickly. Animals of the same species may respond differently to the same treatment, adding complexity to each case. Some patients may take longer to be healed completely, while sometimes, all that is needed is basic care, like giving them a quiet, dark place to rest, eat and drink.

“A lot of times, you think: If I'm helping an animal, it means I must do something for it. But sometimes, the more I do, the more stressed the animal gets; and some of them just need rest,” one vet explained.

At the Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation, birds constitute the majority of animals cared for, coming in with injuries of varying severities. But when resources are scarce, birds must also contend with the other animals for care. Even as vets strive to care for every animal that comes through the Centre’s doors, sometimes difficult decisions must be made.

For example, after surveying their patients for the day, the vets need to prioritise animals in need of urgent treatment, such as an eagle needing a wing fracture repair over a civet with a superficial skin wound.

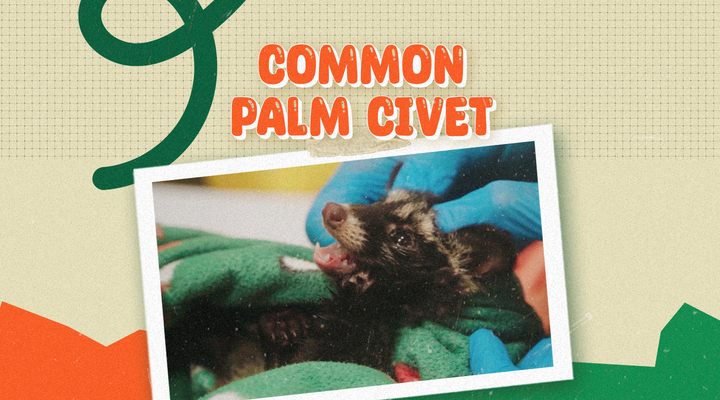

Patient 04: Common Palm Civet

As the civet curls up in the darkness of a towel, a vet carefully examines it for parasites and tends to its injuries. Likely abandoned by its mother, the injured civet offers little resistance, moving slowly and limply as it is assessed for further care. While the vet shuffles through its fur, he explains that beyond tending to native animals like the civet, attending to non-native wildlife is not uncommon.

With the emergence of social media platforms like Telegram facilitating black market deals, exotic animal trade has become more commonplace in Singapore, with a growing number of exotic pet owners in the country.

Not only does exotic trade negatively affect Singapore’s biodiversity, but it also exposes native animals to new diseases and overpopulation. For exotic animals smuggled in, the Centre rehabilitates any injured wildlife and assists in initiatives that help them find new homes, such as rehoming them to the Singapore zoo and other wildlife parks in the country.

On top of managing the operations of the Centre and ensuring that all animals are cared for, the vets at the Centre also participate in the national biosurveillance framework for wildlife, which is a programme dedicated to monitoring, detecting and preventing the spread of diseases of concern within Singapore.

Vets also assist in research efforts by collecting samples and conducting genetic tests, which can provide important insights to an animal’s origin for illegal wildlife trade investigations.

What It Takes to Balance Singapore’s Ecosystem

If you’ve seen a family of otters crossing park pavements or pangolins casually walking beside people as they head back home at night, you’ll know that wild animal sightings have become more common in Singapore.

But Singapore’s bustling wildlife scene did not emerge overnight like a miracle. The country’s greening efforts over the past 60 years have allowed it to become one of the greenest cities in the world.

For each link bridge we build to help animals cross roads safely, there is a skyscraper with windows that birds may accidentally crash into. It is up to the vets at the Centre to assist our wildlife as Singapore continues to urbanise.

With the various facets of the job, there is never a dull day at work. As Singapore transforms into a City in Nature, these vets play a crucial role–one that we often don’t fully appreciate until we pause to observe the nature around us.

“This role has led me to see the bigger picture of things, and because of that, I feel more fulfilled in the work I do,” one of the vets shared.

What Should You Do if You Encounter a Wild Animal?

- Take note of the dos and don’ts when you encounter wildlife in our City in Nature.

- If you spot sick or injured wildlife, you can call the NParks Animal Response Centre at 1800-476-1600.

Want to get more stories like this? Join our Telegram channel https://t.me/psdchallenge.

- POSTED ON

Sep 3, 2024

- TEXT BY

Jayme Teo

- PHOTOS BY

Joshua Yeo