"Nincompoop", "Strawman", "Clown": How Every Word Uttered In Parliament Is Recorded For Posterity

4.5-minute read

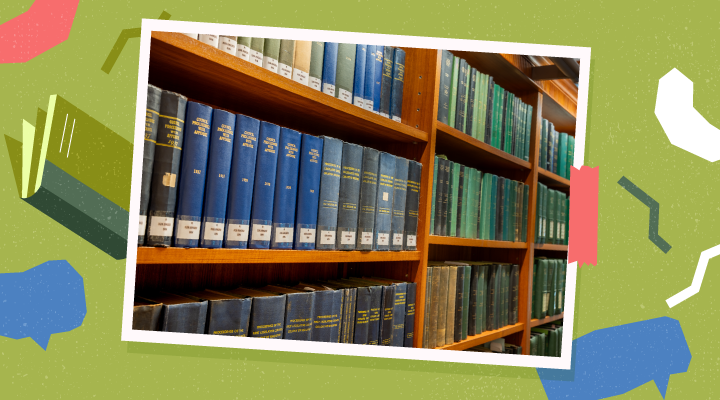

Parliamentary sessions are often dismissed as tedious or routine—but what an unfair stereotype! Dive into decades of Hansards, the official transcripts of parliamentary proceedings, and you’ll uncover a treasure trove of human drama, fiery debates, and deeply emotional moments.

Take then Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam’s wise advice to a fellow parliamentarian to avoid “strawman arguments”. Or former Minister of Education Ong Eng Guan’s remark in 1964 that flats would be built even if the Chairman of Housing Development Board “might be a nincompoop who does not understand the difference between a brick and a stone.”

And one of our favourite moments? The 1956 Assembly Sitting where the Speaker of the House sternly reminded a young parliamentarian, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, that the assembly was not a place where he could “clown and shout out slogans, however commendable they may be”, after Lee jumped up shouting “Merdeka!” mid-session.

Taking down every utterance for posterity

Behind the voluminous reports generated after every Parliamentary Sitting is the five-person Official Reports Department, dubbed “Hansard team”. The term “Hansard” came from Thomas Hansard, the first official printer to the parliament at Westminster, U.K.

These dedicated officers make sure that the transcribed proceedings, as near to verbatim as possible, are sent out to all Members of Parliament (MPs) within 24 hours of a sitting adjournment. The verified Hansard report would be published on the Parliament website seven working days thereafter.

The team also transcribes for Select Committee meetings, such as those of the Public Accounts Committee and the Estimates Committee. Transcribing is gruelling work. To make sure that their work is accurate, the team takes turns to transcribe in 15-minute takes. At the end of the sitting, the 15-minute takes are then collated into a complete report. Talk about teamwork!

From shorthand to AI

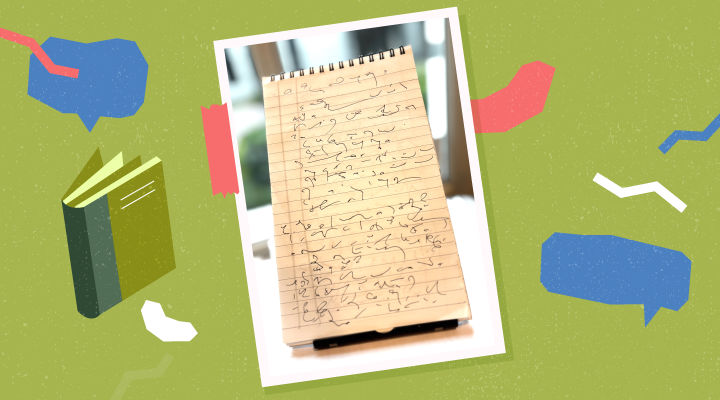

Before the days of transcribing software, it was a must for Hansard team members to know shorthand, a system of rapid writing using symbols. Koh Kiang Chay, who joined the department in 2000, recalled that he and his colleagues would take turns to sit in the Chamber to notate and record in shorthand before typing them out later.

Today, AI-enabled auto-transcription software and technological advancements have made transcription much less menial, and enable a faster turnaround time.

Video and audio recordings of sittings are now transmitted directly to the workstations of staff and the transcription software, Transcribe by GovTech, generates a raw take, which is then edited by the team.

The Open Product Government team at GovTech has also developed the AI-enabled Pair Search platform to perform smart searches across Hansard reports from 1955 to the present.

"Wa meng ti", poignant anecdotes, and the longest session in history

Technology, however, can only go so far. Singapore is a multicultural and multi-linguistic society and that comes through in our parliamentary proceedings as well. Francine Ting, Hansard team’s youngest member and a millennial, shares how confounding the work can be.

“It is not uncommon for our MPs to switch between official languages or make the occasional reference in Chinese dialects. For example, I read that during the 2011 Budget Statement debate, one former MP quipped ‘ai piah jia eh yia’ (Hokkien: One succeeds only when one works hard), and ‘wa meng ti’ (Hokkien: I ask the heavens) in the same breath,” she quotes.

“I’ve also since added words such as ‘prima facie’, ‘pari passu’, and ‘highfalutin’’ to my vocabulary thanks to my work!”

What moves Francine most are the stories of people shared in Parliament, when MPs share accounts of themselves, their residents, and people who overcame adversity through determination.

She says, “These anecdotes offer very relatable, and often personal insights, for example, Minister for Health Ong Ye Kung’s sharing on how patriarchal views have shifted over time in his family, or MP Dennis Tan’s experience as an adoptive parent.”

These moments keep officers like Francine going even when sittings go on indeterminably, such as the historic debate on foreign talents, immigration, and Singaporean livelihoods in 2021 lasting 13 hours and 33 minutes, breaking the 1961 record of 13 hours and 25 minutes. Fortunately, shorthand note-taking was phased out by then.

Preserving democracy, one word at a time

History, as it is said, is the lifeblood of a nation. Hansards stands as its pulse, a verbatim chronicle of how policies and governance evolve. These records are more than words: they hold parliamentarians accountable and safeguard Singapore’s democracy.

The weight of their work becomes most apparent when MPs in the Chamber say, ‘Check the Hansard!’ in the heat of their debates. Aside from the motivational boost, the team is well aware it’s not their hard work alone.

The Hansard reports also represent the work of generations of public officers who had crafted the policies and laws in the first place, and then worked with the Hansard team to clean up typos, misspellings and mishearings in the reports.

Today, Hansards are fully digitised and searchable online, offering a valuable resource for public officers, researchers, and curious citizens alike. The professionalism of the Hansard team ensures that every detail is captured with precision and integrity.

As part of a proud tradition of record-keeping across Commonwealth Parliaments, Singapore’s Hansard team is a member of the Commonwealth Hansard Editors Association (CHEA), maintaining global standards of excellence.

Veterans like Koh Kiang Chay dedicate themselves to mentoring the next generation of Hansard staff, passing on a legacy of meticulous record keeping. Their work embodies the enduring power of words and the significance of preserving them. In every page of Hansard, the voice of democracy resonates, reminding us that history is not just recorded—it is actively written, word by word.

Until the 1900s, reporting parliamentary debates in the British empire was punishable by fines and imprisonment. The rise of newspapers from the 1700s increasingly challenged the ban, leading to Britain’s first official report of proceedings in 1909. Today, Hansards are a critical part of transparent governance in Britain and former colonies including Singapore.

- POSTED ON

Feb 25, 2025