Coral reef biologist Dr Karenne Tun is devoted to protecting Singapore’s coastal and marine biodiversity. Challenge follows the avid diver on a day out at sea.

Dr Karenne Tun developed an interest in coral reefs when she started diving in 1990. “From the first time I descended into a reef environment in Pulau Aur … I was mesmerised by the sheer colour and grandeur of the reefscape. It was love at first sight, and I’ve not looked back since.”

If Dr Karenne Tun had her way, she would dive into work every day. But the deputy director of the National Parks Board’s Coastal and Marine team from the National Biodiversity Centre gets to hit the waters only once a month these days — if she’s lucky.

Still, the water baby (diving since 1990, “when we were still wearing the horse-collar buoyancy control device — bet no one has heard of it, right?”) has a job she loves.

The team sets off for the Sisters’ Island Marine Park from the Republic of Singapore Yacht Club.

She and her team of 11 look after Singapore’s coastal and marine matters to safeguard native sea life. These range from investigating unexplained wild fish deaths, to assessing the responses of marine life to environmental stressors such as elevated sea surface temperature and sediments. As the head of the unit, she’s often at interagency meetings to resolve the wide-ranging issues they face.

Today — that lucky day of the month — Dr Tun and two staff are at the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park to deploy the Monitoring Pulse Amplitude Modulation (PAM) fluorometer under water. They anchor the machine onto a rack they built, before laying out six probes onto two giant clams and four corals nearby.

Dr Tun prepares the scuba diving tank before her dive at the Sisters’ Island Marine Park.

The PAM, simply put, measures how efficiently algae (that live within the tissues of corals and other photosynthetic reef organisms) produce “food” through photosynthesis. It gives early warnings if the algae and their host organisms are stressed by environmental changes, such as warmer waters triggered by El Nino. In response, scientists can protect the most vulnerable coral species by moving them elsewhere until the water temperature returns to normal. If nothing is done, the corals get “bleached” and may die if conditions do not return to normal quickly.

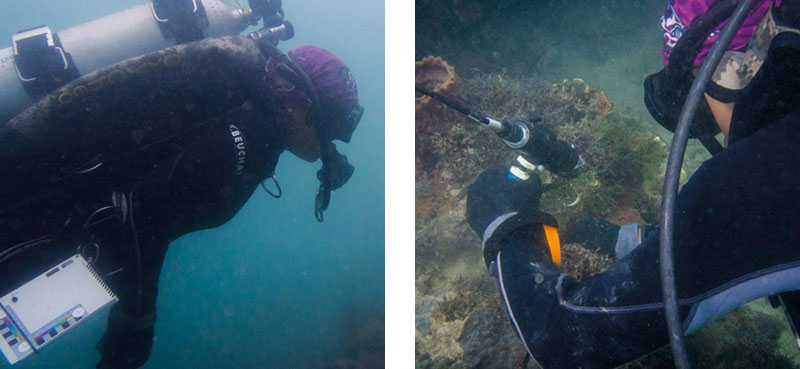

Dr Tun takes the plunge. Once underwater, she will anchor the PAM and set up probes with sensors that emit light at various times to measure how efficiently the algae on corals produce food.

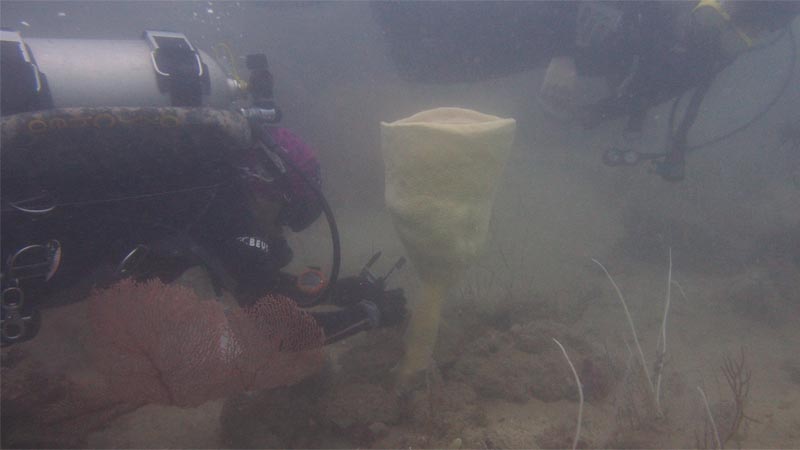

After the PAM is deployed, Dr Tun fins over to a nearby Neptune’s Cup Sponge and begins removing debris that had fallen into its “cup”. It is especially close to her heart as she had rediscovered the species — not seen since 1908 — in 2011 while working for an environmental consulting company. She recounts animatedly that when she swam by the young, oddly shaped sponge, her sixth sense prompted her to cut a small block of the sponge out for analysis, and that led to the rediscovery of the species.

After working on coral reef biology, ecology, conservation and management for over 20 years, this portfolio allows me to apply all my knowledge and experience to establish a marine park that can be a model for other marine parks around the world. It was too good to pass up

Two years after that thrilling discovery, Dr Tun took the plunge and joined the public sector, lured by the opportunity to establish Singapore’s first marine park at the Sisters’ Islands, which opened in late 2015.

“After working on coral reef biology, ecology, conservation and management for over 20 years, this portfolio allows me to apply all my knowledge and experience to establish a marine park that can be a model for other marine parks around the world. It was too good to pass up,” she says.

Left: Dr Tun fins towards the survey site with the PAM. Right: Dr Tun sets up one of the six PAM probes.

The team does everything from handling tenders and vendors, to scientific research and public outreach in raising awareness of the biodiversity in Singapore waters.

The numerous projects and heavy workload Dr Tun and her team manages daily hasn't dampened her spirit: “As long as I wake up each day thinking, ‘What can I do today that will make a difference to the coastal and marine environment in Singapore?’, I know that I am in the right job. And that, is my motivation.”

Before heading out for the dive, the team picks up their dive gear and the PAM machine from the store room at National Biodiversity Centre.

From left to right: Dr Tun, Collin Tong (Senior Manager, Biodiversity), and Koh Kwan Siong (Manager, Biodiversity) prepare the PAM fluorometer for its underwater assignment.

The team checks to make sure there is no dirt or hair on the sensors and that every part of the machine is sealed and waterproof.

Simply put, the PAM measures how efficiently algae (that grows within the tissues of corals) make “food” through photosynthesis. It gives early warning to scientists if the coral reef is stressed from environmental stressors like pollution or warming waters.

Dr Tun fins towards the research site with a PVC rack they had built to secure the PAM machine. “We get to build stuff that no one else is interested in producing,” she says, adding that their office has a small workshop for such DIY work.

Before anchoring the PAM, the team makes a few adjustments to the PVC rack. Hammering and sawing underwater has now become second nature to them.

Dr Tun secures the PAM onto the rack with cable ties. These days, she considers working underwater more exciting than recreational diving. She shares that the team had perspired while installing signboards for the Marine Park’s Dive Trail underwater!

The PAM is secured and its cables carefully bagged up. The sturdy machine is left underwater for a few weeks to gather data.

Kwan Siong holds one of the PAM’s six probes.. Each probe is attached to a 10m cable, which allows divers to spread out the probes underwater to survey a larger area.

Dr Tun points a probe towards a giant clam.

The sensor of the probe emits light at various times and measures how efficiently the algae within the tissue of the giant clam produces “food”.

Another probe is installed next to a foliose hard coral to monitor how the algae within the host organism responds to light.

After installing the PAM machine, Dr Tun stops by to say “hello” and check in on the Neptune’s Cup Sponge.

Dr Tun has a soft spot for the Neptune’s Cup Sponge, having rediscovered the species in 2011. She picks out debris that had fallen into the sponge’s cup-like receptacle and jokes that she often does “janitor duties” underwater.

This young Neptune’s Cup Sponge, transplanted from Semakau Lagoon in early 2015, is growing well. According to Dr Tun, it’s grown about 10cm in height since its relocation, and a bite mark from a hungry turtle has also healed.

Two Neptune’s Cup Sponges are now at the Marine Park. Dr Tun hopes they will “mate” and produce offspring by cross-fertilisation when they spawn.

Dr Tun prefers diving in tropical waters, as compared with temperate waters, as the marine biodiversity is richer. Pictured here is a featherstar.

She points out that the sea fan coral (pictured) doesn’t create food through photosynthesis; it depends on water currents to bring it “food” such as plankton. Hence, an aggregation of large numbers of sea fans, which is typical at the Sisters’ Islands, indicates that an area has strong currents.

It’s a wrap. After an hour or so underwater, the team have exhausted their air supply and call it a day. They’ll be back in a few weeks to retrieve the PAM and its data.

Taking care of Singapore’s marine and coastal biodiversity can mean working long, atypical office hours. But Dr Tun has no complaints: “Confucius once said, ‘Choose a job you love, and you will never have to work one day in your life.’ I can closely relate to it as work you love will no longer become a chore but a process. In fact, it’s likely that you will end up working more, only because you want to and not because you’re required to.”

.tmb-tmb450x250.jpg)