WorkRight Campaign: Helping Workers Fight For Their Employment Rights

The breakfast crowd at the Tiong Bahru Food Centre was given a surprise early last year, when a flash mob broke out with a cleaning auntie and elderly folk singing and dancing – to the Hokkien song Ji Pa Ban (“a million dollars”).

As the audience whipped out their phones to capture the show, the performers exhorted them to help any workers they know who were not getting their entitled employment benefits, such as sick leave and Central Provident Board (CPF) contributions, by calling a hotline.

The staging was part of WorkRight, a joint campaign by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and the CPF Board to raise awareness of workers’ rights in Singapore.

It went on to attract much attention online: a video of the performance has had more than 190,000 views on YouTube.

Besides hitting the right notes with the public, the creative outreach idea has also helped the campaign win global recognition: in June, WorkRight won first place in the “Promoting Whole-of-Government Approaches in the Information Age” category for the Asia-Pacific region at the 2015 United Nations Public Service Awards – a first for Singapore.

Mr Raymond Tan, who heads the WorkRight Programme Office running the campaign, says the team of MOM and CPF Board officers spent many hours brainstorming how to get their message across to low-wage workers, whom Singapore’s employment laws are meant to protect.

Until then, there had been no concerted effort by the government to promote employment rights under one campaign.

“There was some reflection on our part,” says Mr Tan, Director of Employment Standards Enforcement at the MOM. “We’ve had the Employment Act and CPF Act for quite some time, but why are there still workers who do not know what they are entitled to under the law?

“So we felt we needed to pool our resources together to do something that has never been done before, to raise public awareness of the employment laws.”

Education and access

One of the first things the team quickly agreed on was that education and enforcement had to go hand in hand.

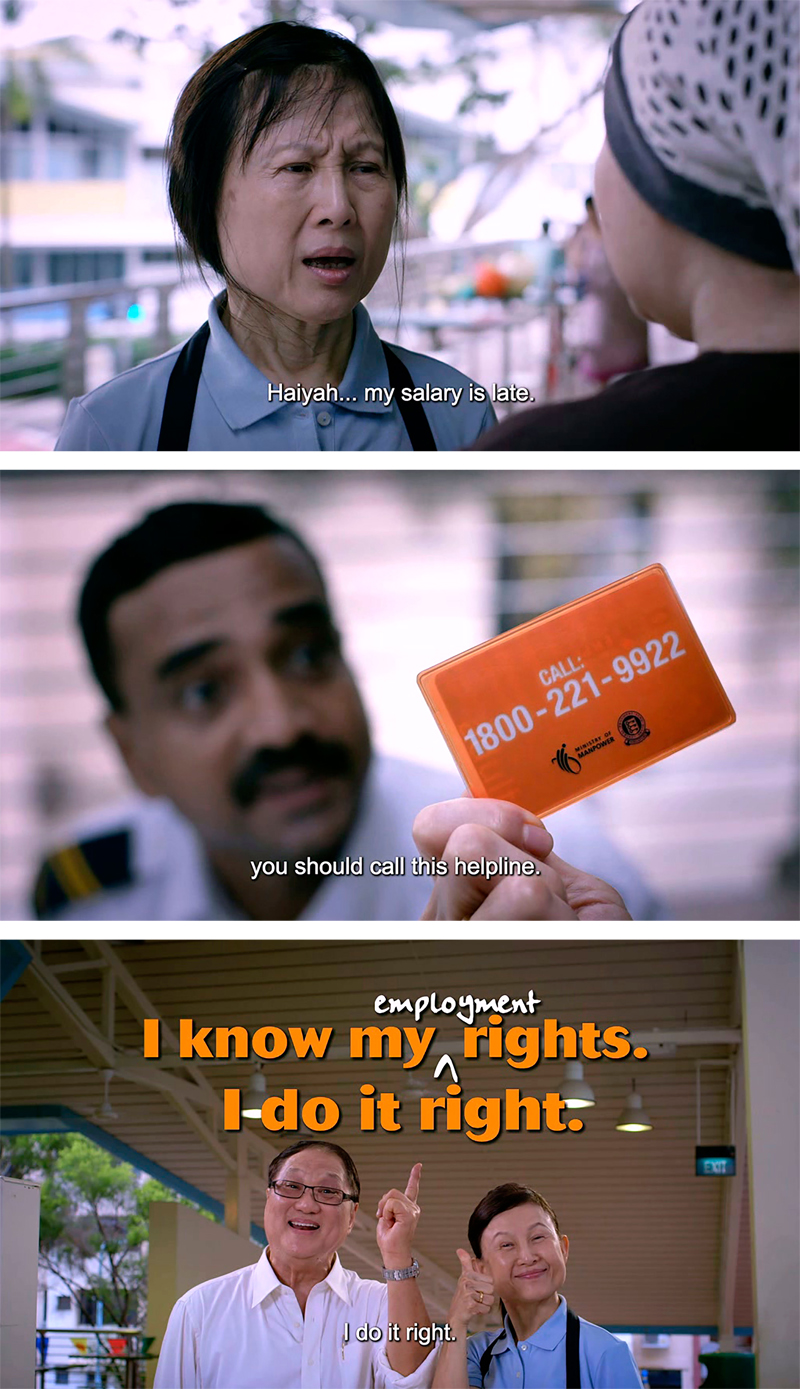

In their first phase of public engagement, they launched a mass media campaign, running advertisements in newspapers, radio, TV and public spaces, with an easy-to-remember tagline: “I know my rights. I do it right!”

They also set up a WorkRight hotline and email address for workers and their families to lodge complaints. Previously, complaints had to be made separately to the MOM and CPF Board. The hotline and email address together now receive an average of 1,700 enquiries and complaints every month.

To reach workers and employers directly, the team stepped up their ground inspections tenfold to 5,000 a year, targeting industries more likely to have cases of not complying with employment laws, starting with cleaning, security and retail.

Besides addressing areas of non-compliance, the WorkRight inspectors would take time during their visits to educate both workers and employers about their rights and obligations.

This approach proved so effective that the level of compliance among employers improved from 70% in 2013 to 90% in 2014.

Food service distributor Food Xervices was one of the companies that had to review its employment practices, after WorkRight inspectors found that the company was not providing enough sick leave for its staff.

While inspections often strike fear in business owners, Managing Director Nichol Ng says she appreciated the softer approach that the WorkRight inspectors took. “The officers weren’t here with a bone to pick, but to share with the people on the ground what’s really needed to comply with the laws,” she says.

One of the employees, Customer Service Executive Emily Koh, agrees. “The government is taking the time to check the issues on the ground, which safeguards our well-being,” says the 25-year-old, who is diabetic and now has adequate sick leave for medical appointments.

Beyond the tried and tested

Building on the momentum, the team went on to target the heartlands and social media in phase two of their campaign.

This was where the team “experimented a lot” – from sticking decals on tables in coffeeshops and foodcourts, to airing advertisements in hair salons frequented by low-wage workers.

“We talked to the CDCs (Community Development Councils) and self-help groups to tap their estate knowledge and find out where the community will congregate,” says Mr Tan.

The flash mob move had pushed the envelope, since most government agencies had not used dialects such as Hokkien, and Singlish, in a national campaign.

The team overcame their reservations to go ahead. Seeing the results now, the gamble was “worth it”, Mr Tan says.

“Within the government agencies, some people have also told us we have done very well [with the flash mob idea].”

Early this year, the team also targeted a secondary, more tech-savvy audience with a touching advertisement, on the hopes of low-wage workers to have their basic employment rights met, launched on social media.

The video, which has been viewed about 14,000 times, has helped to mobilise the children, relatives and neighbours of low-wage workers to call the WorkRight hotline on their behalf.

Collaboration works

If there is a lesson that Mr Tan has taken away from working on the campaign, it is this: “The future of public service is not limited to contributions by public officers.”

“Although we started with a whole-of-government approach, we ended up with a whole-of-society approach,” he says.

“Whether it was to reach out to low-wage workers in the heartlands or influencers on social media, there were a lot of discussions and working with the public, private and people sectors. Everyone helped to carry out this public service.”

Far from resting on their laurels, the team is already planning their next move. This includes sending WorkRight “mobile clinics” into the heartlands to directly help workers and employers with employment issues, rather than waiting for workers to call the hotline.

Going by the campaign’s success so far, they are on the right track.

- POSTED ON

Nov 9, 2015

- TEXT BY

Jamie Ee