Game Changers: Improving Public Services With Play

If returning trays after eating was fun instead of a chore, more people might clear their tables at food courts. So a team of public officers explored making the act of cleaning up enjoyable by turning it into a game.

They came up with The Speedy Sorter, a series of game stations that weighs your food waste; instantly crushes drink cans; has cut-out holes for plates, utensils and trays; and rewards you with a small item like a can of drink for taking part in the game (and for your act of courtesy).

This prototype game was cooked up during XEOPlayshop, a workshop that offers creativity training and techniques to enhance user engagement and experiences through game-design thinking.

Organised by the Civil Service College (CSC) and taught by renowned game researcher and designer Nicole Lazzaro, the two-day workshop in July drew 25 participants from various agencies. They learnt about game principles and then created “serious fun” games related to the Public Service using those principles.

Why Play?

Different from the typical games played primarily for entertainment, these games have a clear educational and engagement purpose.

Such games-inspired thinking provide opportunities for improving public services by spreading messages faster and inspiring changes in behaviour, says Ms Lazzaro, president of consultancy XEODesign.

Ms Lazzaro has advised the White House and the US State Department on the use of serious games in public service. She identified five areas where gaming principles are particularly useful: education, health, public transport, government procurement, and civic participation and engagement.

For instance, such games can get people moving to improve their health. The Zombies, Run! app makes running an immersive adventure with a soundtrack of zombies chasing you as you run. In First Lady Michelle Obama’s campaign to end childhood obesity, apps like Work It Off teach children about healthy eating and exercise habits.

Here at home, the Incentives for Singapore’s Commuters (INSINC) web app encourages commuters to use the trains during non-peak hours, an example of gamification potentially changing behaviour. Gamification is the application of game-design thinking to non-game applications to make them more fun and engaging (read Fun Is The Future Of Work in our November/December 2012 issue).

Games are the new medium for the 21st century, says Ms Lazzaro. Modern citizens face issues such as global warming, economic crises, viral diseases and recently in Singapore, the haze from Indonesia. These problems all have multiple cause-and-effect relationships, she says. “We have to teach them systems thinking somehow, so why not teach through games?”

Instead of informing, say, about mosquito breeding through static PDFs or brochures, she says “you could get your message across much more quickly if you had a good interactive experience to communicate what’s going on.”

Educational games can also teach empathy and real-world problem-solving skills, particularly through role-playing and simulation. For instance, a city-building game similar to SimCity could show what it takes to develop and maintain an urban town. “The purpose of play is to invent our future selves,” says Ms Lazzaro. Through games, you could practise multi-tasking, interacting and teamwork, and, “if you become the mayor of SimCity, then you have mastered the content of what it takes to be a city manager.”

Games can inspire people to learn new things without being intimidated by the prospect of failure. To encourage entrepreneurship, Ms Lazzaro suggests a game where users can role-play being an entrepreneur. In the game, you can simplify the role of an entrepreneur, suspend consequences, and provide constant feedback on how well the user is faring.

Making Play Work

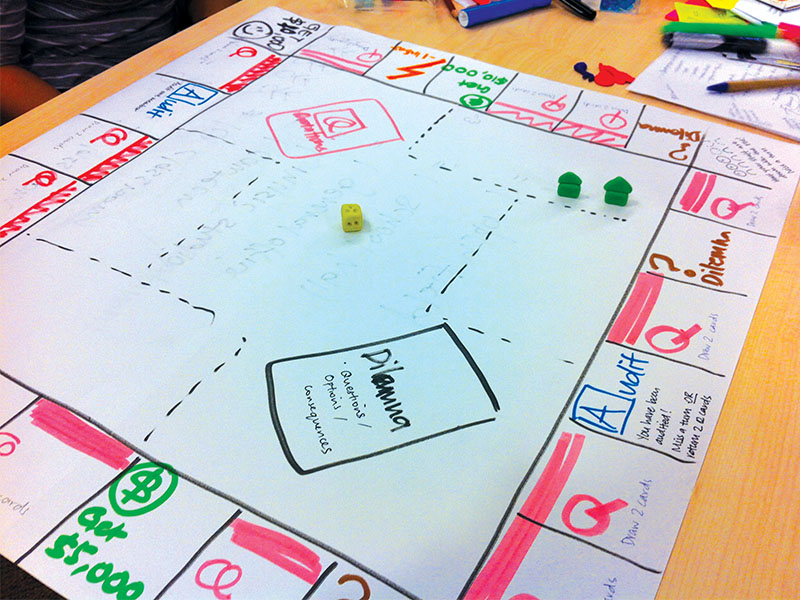

During the XEOPlayshop, participants identified public services or policy problems where game-design principles could be applied. In teams, they designed games based on a chosen issue using a G.A.M.E framework – identifying goals, actions, motivations and emotions – and then built prototypes to rapidly test their games.

Their games included potential projects for citizens. The team behind The Speedy Sorter aimed to solve the real issue of getting citizens more involved in cleaning up after eating. There were also games for training public officers about procurement principles (in a game similar to Monopoly), budget constraints (players have to manage a virtual airport in dire straits) and policy trade-offs (a mosaic puzzle game on land use allocation).

The officers used Ms Lazzaro’s Four Keys to Fun framework, a tool to design interactive systems. From 20 years of research and observing gamers’ emotions during play, Ms Lazzaro found that games offer four types of fun: Hard Fun, Easy Fun, People Fun and Serious Fun.

Over time, games have to increase in difficulty, or players will get bored and quit. “Contrary to popular belief, making a game is really, really hard,” Ms Lazzaro says wryly. Increasing game difficulty is more than “adding monsters and reducing time”, or requiring players to collect more points. “It’s very challenging to make a game more difficult by changing the strategy... In that hotbed of innovation, game designers have invented all kinds of ways to engage the human psyche.”

Four Keys to Fun

According to Ms Lazzaro, games offer four types of fun that create emotions and engagement. Bestselling games comprise at least three of the four play styles:

EASY FUN

Novelty that creates curiosity and wonder – people first get hooked onto games because of Easy Fun.

HARD FUN

Challenge that creates frustration and fiero – a feeling of personal triumph, or the “epic win”.

PEOPLE FUN

Social interaction that creates feelings of friendship, amusement and rivalry.

SERIOUS FUN

Rewards that create excitement and meaning – this is also where games can make the biggest impact in public service. “We really enjoy games that [enable people to] change themselves or change the world,” says Ms Lazzaro. She developed an iPhone game, Tilt World, which plants real-life trees in Madagascar when players collect enough points.

Ms Daisy Koh, a senior executive at CSC’s Institute of Leadership and Organisational Development who attended XEOPlayshop, says the workshop helps her think of unconventional ways to engage public officers. “Maybe we can do game booths so we can pass down information more quickly and it becomes more interesting to [officers],” she muses.

A frequent gamer herself, Ms Koh appreciates learning about the G.A.M.E and Four Keys to Fun frameworks. “Before this, I thought that games were just games,” she says. “Now I can clearly see how each game is designed to fulfil the four elements.”

Another participant, Ms Caryn Lim, who is deputy director of corporate planning at the Ministry of Manpower, believes that agencies need to try new ways of engagement. But whether to embark on game principles in public service “depends a lot on time and cost”, she points out.

Ms Lazzaro acknowledges that training in game-design thinking and applying that in policies is an investment (and risk). But the cost of not exploring game-thinking is losing out on an opportunity to make your public services more engaging than simply downloading a PDF from your website, she says.

Are you game?

Nicole Lazzaro is president of XEODesign, a consultancy offering 20 years of player experience design for games, educational software and business applications. She is among Fast Company’s 100 most influential women in technology, and Gamasutra’s top 20 women working in video games. She has also written about gaming in public service.

- POSTED ON

Nov 27, 2013

- TEXT BY

Siti Maziah Masramli