From Civil Servant To President

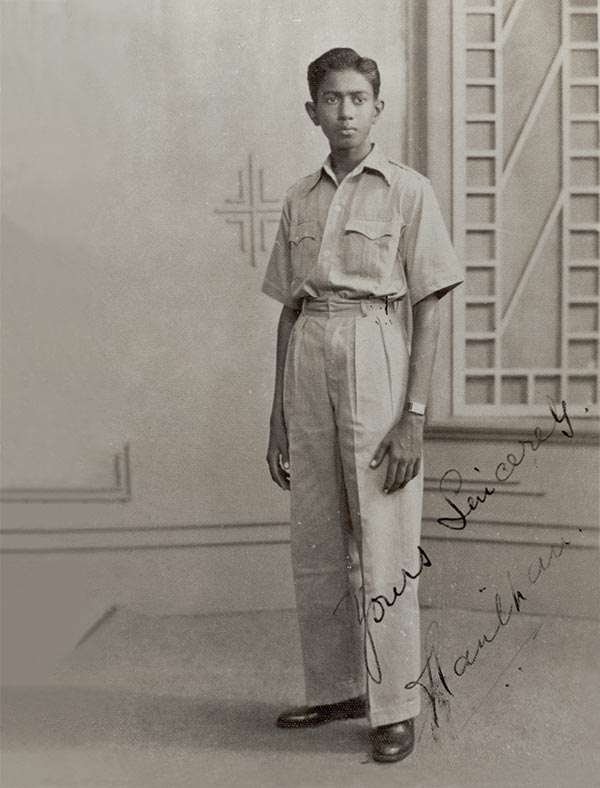

1946

Mr S R Nathan’s civil service career started in 1946 when he joined the then Johor Public Works Department without a diploma; he had dropped out of school before World War II. Here he got involved in negotiations over pay for civil servants, and eventually joined the Johor Civil Service Association, a trade union. At Mr Nathan’s 90th birthday celebrations, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong shared that Mr Nathan, who had long retired from the Johor civil service, continued to draw a small pension from it.

1955

Determined to advance his career, Mr Nathan pursued his “O” Levels as a private candidate, through a correspondence course. For a year, he woke up at 4am to study before going to work. He did well enough to enter the University of Malaya at 28, on a Shell bursary. His was the first cohort to pursue a Diploma in Social Studies.

In 1955, Mr Nathan graduated with Distinction and became a medical social worker at the Tan Tock Seng Hospital. At that time, social workers were known as “almoners”, people who gave away alms. As Mr Nathan was the hospital’s first male almoner, his office door bore the label “Lady Almoner” for some years before it was changed.

1956-1961

In 1956, Mr Nathan sailed into unchartered waters when he was appointed Assistant Seamen’s Welfare Officer by Chief Minister David Marshall. He never knew why he was handpicked but suspected that it was because he had written about the debt enslavement of Asian seamen for his final year thesis. The young civil servant’s job was so new that there wasn’t a job description. Along with a fellow civil servant Mr Goh Sin Tub, who later became an acclaimed writer, Mr Nathan figured out his responsibilities on the job. Eventually Mr Nathan was promoted to be the Seamen’s Welfare Officer.

Once he had to fly out to a cruise ship docked in Panama City as six Singapore seamen were making trouble onboard. Their hooliganism threatened the livelihoods of the other 300 Singaporean crew. Upon arrival, Mr Nathan found that the six were secret society members with guns onboard. He arranged for the police and customs to board the vessel when it docked in New York City so that the ship’s master could discharge the troublemakers safely. After the incident, one of them called at Mr Nathan’s office to warn him to “be careful”.

Mr Nathan’s time as Seaman’s Welfare Officer wasn’t smooth sailing. He faced many unreasonable demands from seamen and employers alike. In fact, then Finance Minister Dr Goh Keng Swee nearly fired him after he failed to save a seaman’s job. Another complaint to Mr Lim Chin Siong (then Political Secretary to the Finance Minister) added to his frustration with the “thankless job”. He contemplated quitting until a Catholic priest, Father Fox, asked the depressed civil servant: “Have you ever asked yourself why you are here?” The question taught him to think of the larger purpose always — a lesson he remembered for the rest of his career.

1962

In the early 1960s, political tensions between the communist and non-communist factions came to an all-time high. The rivalry was echoed in the labour movement, with pro-communist unions forming the Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU) and their opponents, the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC).

Mr Devan Nair, the secretary-general of NTUC, lobbied the government to fund a Labour Research Unit (LRU) to support non-aligned unions as well as units that had left SATU. The support, argued Mr Nair, would prevent the smaller unions from returning to SATU’s fold. The LRU was formed in 1962 as an autonomous institution, staffed by research officers seconded from the civil service as well as trade unionists seconded from the industries.

Once again, Mr Nathan was sent to this new unit, where he would later become Director. Not surprisingly, there was no clear brief of what to do, resulting in a wide range of duties to help aggrieved workers. This time there was an added pressure: he had to grapple with the issue of civil service neutrality as he — a civil servant — had to act on behalf of unions in their disputes with employers. He agonised over this dilemma for a few months before reconciling with his new role. Given the volatile political situation, he saw that his work at LRU was “helping many working people and their families in one way or another.”

1965

Four months after Singapore gained independence, Mr Nathan, 41, found himself at yet another newly formed agency — the Ministry of Foreign Affairs — as an “assistant secretary”, which was a junior civil service position. When he asked Foreign Minister S Rajaratnam what foreign policy principles he should follow, the reply was: “Don’t worry, it will come naturally”. Yet again, he had to improvise on the job.

In 1967, he witnessed the challenges Mr Rajaratnam faced in setting up ASEAN when he accompanied the minister to an informal ministers’ meeting in Bangkok. The junior officer was waiting outside when he was summoned to take the minister’s files away midway through the meeting; Mr Rajaratnam had wanted to leave as the ministers could not agree over the presence of foreign military bases in ASEAN. Persuaded to stay by the Indonesian foreign minister, Mr Rajaratnam managed to convince the others that the foreign bases were important for regional security many hours later.

1974

Mr Nathan’s most dangerous assignment took place in 1974 when he was director of the Security and Intelligence Division at the Ministry of Defence. When a group of Japanese and Palestinian terrorists failed to blow up Shell’s oil tanks on Pulau Bukom, they hijacked the company’s Laju ferry and threatened to kill the hostages unless they obtained safe passage to a Middle Eastern country.

After lengthy negotiations, they agreed to be flown to Kuwait via Japan Airlines with a demand to be accompanied by unarmed teams of Singaporean and Japanese officials. Mr Nathan, who led the Singapore team, did not share his fears with his family but he was afraid that they would become bargaining chips in Kuwait. Upon arrival, Mr Nathan insisted that the team leave the aircraft before another group of terrorists, who had stormed the Japanese embassy in Kuwait earlier, boarded the plane. This negotiation took hours. When the Singapore team managed to leave the aircraft, they quickly hopped onto another plane and headed home. The terrorists were flown to South Yemen and the episode ended without bloodshed. When asked by a reporter how he remained calm, Mr Nathan replied: “Because I am a trained social worker.”

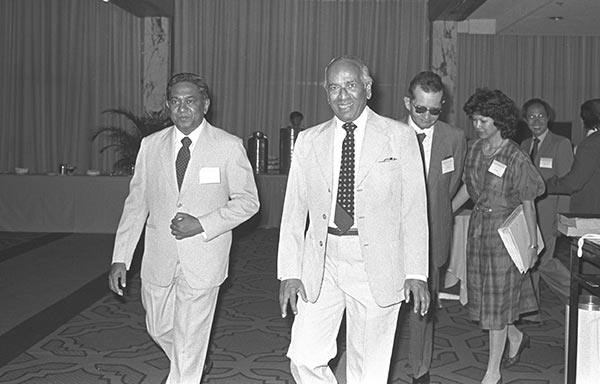

1979-1982

In 1979, Mr Nathan was transferred back to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and became its first Permanent Secretary until 1982 when he officially retired from the civil service.

Mr Nathan took on directorships in several organisations until 1988 when he was appointed High Commissioner to Malaysia. In July 1990, he became Ambassador to the United States of America where he served until June 1996.

1993

When American teenager Michael Fay was sentenced to be caned for vandalism and theft, Mr Nathan was Ambassador to the US in Washington DC. He had to break the news to the White House when the plea for clemency from caning was rejected. Mr Nathan also went on Larry King Live to explain Singapore’s position.

When The New York Times called for the public to protest by calling the Singapore embassy, the embassy set up an automatic answering system to gauge public sentiments. Callers could either register opposition to punishment (“Press 1”) or to indicate their support (“Press 2”). The embassy found that more people called in favour than opposition. When the embassy received a voice message that threatened to kill Singaporeans if Michael Fay was harmed, Mr Nathan was placed under the US Secret Service Protection.

1999

For personal reflections on Mr Nathan from two of his Principal Private Secretaries and his first female full-time Aide-De-Camp when he was President, visit the links below:

Sources

1. PM Lee Hsien Loong's Speech at Mr S R Nathan's 90th Birthday Celebrations, Singapore, Prime Minister’s Office, 2014.

Available online: https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/media-releasepm-lee-hsien-loongs-speech-mr-s-r-nathans-90th-birthday-celebrations

2. Citation for the conferment of fellow to S R Nathan, Singapore, Singapore Association of Social Workers, 2008.

Available online: http://www.sasw.org.sg/swd2008/Citation_for_SR_Nathan.htm

3. Citation for the conferment of fellow to S R Nathan, Singapore, Singapore Association of Social Workers, 2008

Available online: http://www.sasw.org.sg/swd2008/Citation_for_SR_Nathan.htm

4. S. R. Nathan and T. Auger. S R Nathan 50 stories from my life, Singapore, Editions Didier Millet, 2013, p 95

5. S. R Nathan, Why am I here? Overcoming hardships of local seafarers, Singapore, Centre for Maritime Studies, National University of Singapore, 2010, p 59

6. S. R Nathan, Winning against the odds: The Labour Research Unit in NTUC’s founding, Singapore, Straits Times Press, 2011

7. S. R. Nathan and T. Auger. S R Nathan 50 stories from my life, Singapore, Editions Didier Millet, 2013, p 117

8. S. R. Nathan and T. Auger. S R Nathan 50 stories from my life, Singapore, Editions Didier Millet, 2013, p 138

9. Citation for the conferment of fellow to S R Nathan, Singapore, Singapore Association of Social Workers, 2008

Available online: http://www.sasw.org.sg/swd2008/Citation_for_SR_Nathan.htm

10. S. R. Nathan and T. Auger. S R Nathan 50 stories from my life, Singapore, Editions Didier Millet, 2013, p 156

- POSTED ON

Aug 23, 2016

- TEXT BY

Bridgette See