Behind the Scenes of Our Singapore Conversation

This August, Singapore wrapped up its largest-scale citizen engagement exercise, Our Singapore Conversation (OSC). As it turned out, articulating its objectives – getting Singaporeans to discuss the challenges facing Singapore and the nation they wanted to see in the future – was the easy part.

The challenge lay in the “how” – how to come up with a format suitable for the many varied dialogues that would make up OSC, shared Mr Nicholas Thomas, a senior executive from the Civil Service College (CSC). He was a member of the OSC Secretariat, which comprised public officers seconded from various agencies.

“The mental model was that of a town hall – with rows of seats and a big hall setting. But that was not what we wanted,” said Mr Thomas. “We wanted something where people held conversations with each other – this was an important guiding principle in developing the [eventual dialogue] model.”

An evolving format

To kick-start the process, facilitators from both public and private sectors were invited to take part in prototyping sessions. They envisioned Singapore in 2030, and articulated these ideas into mock newspaper headline stories.

Five prototyping sessions later, the final model was developed: participants would start discussions in small groups, then come together in a larger group dialogue before breaking up into small groups again. This format was ideal for warming people up and getting multiple views. The role of facilitators was also critical – “to provide a safe space for participants, help them share from the heart and to address conflicts,” he said.

With the dialogue model pinned down, a final prototyping session was held nine days before the public dialogues were launched. “We shared with [our colleagues] what we thought was a good product. But they tore it apart,” Mr Thomas recalled with a chuckle. “It was challenging for the team because we were so close to launching it!”

But it was in this session that many important aspects were fine-tuned. “We learnt a lot. People said: ‘Don’t put the camera too close to my face’, ‘There shouldn’t be so many note-takers so close to me’ and ‘There are too many observers’ – small things like this mattered when we took it public.”

Based on the feedback, they also included an icebreaker where participants were paired up and encouraged to share a story with their partner, and then tell the group about one another. This set the scene for better mutual understanding and hopefully, greater empathy.

Another major change was to get participants to share their present concerns first before they went on to envision the future and to think of ways to get there. This allowed people to express their current views or even frustrations early on in the process.

These tweaks helped create a trusting space for the public so they felt secure enough to speak, said Mr Thomas. Even after the dialogues had started officially, the Secretariat continued to tweak the dialogue format based on feedback from “the dedicated pool of volunteer facilitators.”

Engagement in action

Mr Raizan Abdul Razak, a volunteer facilitator who works at the Ministry of Education said: “It was useful to learn how the sessions were structured and how the issues were teased out…” For him, the most important outcome of the OSC was the opportunity to build a culture of dialogue and to be comfortable with disagreement.

Ms Feng Chunling, an assistant manager at CSC, facilitated four OSC dialogues. She recalled being anxious during the briefing before the first session. “When the other facilitators talked about how to handle difficult or aggressive people, I got nervous… Citizens have come down rather harshly on the government in the past few years, so I was worried it would be a government-versus-people scenario.”

Thankfully, her fears were unfounded. “I saw that citizens were willing to share and there was a surprising range of different opinions. Beyond that, the folks in my groups actually took the initiative to prompt one another for clarifications and explanations for their views. There were times when I felt the conversations could have taken place without my presence, and that is the true essence and meaning of conversation,” she said.

Reflecting on OSC

One major outcome from the sessions, said both Mr Raizan and Ms Feng, was the sense that people came away feeling that they had been heard and they had gained a better understanding of issues. This was not only in an increased awareness of understanding the intricacies of policies and policymaking, but also of the diverse opinions and aspirations of others.

Said Ms Feng, “[The sessions] dispelled my fear that people would see this as a fake exercise; they were really sharing their views.”

For Mr Thomas, the enthusiasm shown by participants and volunteer facilitators alike dispels the notion that Singaporeans are an apathetic bunch: “There was this sense of pride; people were taking it seriously. What it means is we should really have more channels for engagement.”

Facilitation insights from the OSC Secretariat

The sweet spot

Eight is more than a lucky number – it’s the ideal number for a small group discussion. Any more and people tend not to have enough time to talk.

Have a rough plan

A facilitation plan with a structure of the essential questions helps. Use it as a guide but be flexible.

Get participants prepared

Hand out brief notes (e.g. statistics) on related topics before dialogue sessions for more meaningful discussions.

DUA (Don’t Use Acronyms!)

Avoid mysterious acronyms wherever possible – or at least explain them first! Too many acronyms slow down the conversation.

Be adaptable

Adjust to the needs of each group. At a youth dialogue, the facilitation plan included an hour of trust-building activities before starting the conversation.

Dig deeper

Ask for the reason behind a certain stand. People may agree on the same thing, but have different reasons for doing so.

Everyone is equal

Treat all present as equal participants. The OSC small group dialogue format made interactions between citizens and VIPs more informal. This also enabled citizens to get to know each other better.

Be sensitive about semantics

Some words hold negative connotations even if people agree with the term, in theory. The word “trade-off”, for example, was not well-received so facilitators asked participants “what do we give up or gain”. Be mindful of “gov speak”.

Allow different modes of expression

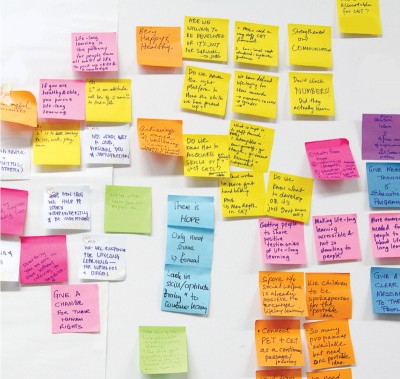

In OSC, some participants drew out their vision of Singapore while others wrote on sticky notes. These were displayed so everyone had, in their own way, a chance to get in a final say.

- POSTED ON

Sep 19, 2013