Make Way for Gov 2.0

Government 2.0 is a sea change in the making – transforming how public servants everywhere listen to, speak with and work with citizens.

This fundamental public service culture change is to enhance responsiveness, relevance and service delivery. Often, technology helps drive more open, transparent government, where citizens play an active role in solving community problems and even shaping policies. Social media such as Facebook, Twitter and blogs are becoming integral, but the key difference is using them in a way people find relevant.

When snowstorms pummelled the northeastern part of the United States last December, New Jersey Mayor Cory Booker, a prolific Twitter user, used the messaging system to update residents about clean-up efforts; he responded to tweets, personally digging out snowed-in cars and delivering supplies to stranded residents. He was hailed as Newark’s ‘one man snow patrol’. As WNYC.org observed, “[Booker] didn’t just reply with a tweet. He also showed up with his feet.”

In Singapore, a five-year e-Government Masterplan is enhancing collaboration in the public sector with better use of technology. According to Minister for Information, Communications and the Arts (MICA) Lui Tuck Yew, this is a shift from a “Gov-to-You mindset to a Gov-with-You direction”.

Noting that more citizens today have higher expectations and are empowered and enabled by social networking, he said in January 2011 at the Singapore GovCamp: “Such profound changes in the nature of technology and demographics will give rise to new models of service delivery – based on collaboration and co-creation with the private and people sectors.”

He cited the OneMap initiative launched by the Singapore Land Authority and Infocomm Development Authority in March 2010. The online geospatial platform allows users to create new applications on a common base map of Singapore and enter information ranging from businesses to recreational activities – a system that, as Muhammad Hanafiah, Director of MICA’s Industry Division, said, aims “to tap the collective wisdom of our netizens, to see how we can further improve on our services”.

The Big Idea: Co-creation

Governments and people need to work better together as agents of change, given the growing concerns of rising costs, ageing populations, immigration challenges, healthcare issues and a sense of division between people and the public sector.

“Co-creation” – or “co-production” – is defined by David Boyle of the UK’s New Economics Foundation and Michael Harris of the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts as “delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours”.

According to Matthew Horne and Tom Shirley in a discussion paper for the UK Cabinet office, collaboration results in faster, more responsive, effective and affordable service outcomes. These partnerships are based on four clear values: “Everyone has something to contribute; reciprocity is important; social relationships matter; and social contributions (rather than financial contributions) are encouraged.”

While it is not a panacea for all ills, co-creation is important for public service, said political observer and Assistant Professor of Law at the Singapore Management University, Eugene Tan.

“[It recognises that] the public sector doesn’t have the monopoly of wisdom and volunteerism may lack the degree of accountability needed for a sustained delivery of high quality public services… [Co-creation of services] is about tapping the social capital within a community while enhancing the stock of social capital in the process.” He added that as society matures, people value non-material concerns more and they “seek self-fulfilment and self-actualisation, and service co-creation offers the segue for deep involvement and a commitment to collaboration.”

In his book Leading Public Sector Innovation, author Christian Bason argues that co-creation hinges on key conditions ranging from context to strategy, organisation, technology, people and culture, and courageous leadership.

“At the heart of all this should, I think, be a culture of trust, where there is a genuine openness and curiosity about how to do better tomorrow than today – not to blame oneself or each other, but to generate more value for citizens and society. Too few public organisations are really characterised by these traits; and it will always be difficult, given the political nature of public organisations and the intense media scrutiny,” said Mr Bason in an email interview with Challenge.

Limits of Co-creation

In their discussion paper, authors Horne and Shirley say that co-production is not appropriate for every service. The greatest potential benefits, they suggest, are in relational services where benefits far outweigh risks. These include areas to do with social relationships such as early childhood education, long-term health conditions, adult social care, mental health and parenting. And in relational services, co-production can deliver the largest benefits where the social issues are chronic and complex, and solutions are contested.

Mr Bason pointed out that there is often a perceived fear of “losing control” and of the rise of “citizen dictators” from co-creation. But ultimately citizens are considered contributors to an innovation process, and decisions are made by larger bodies like steering committees.

“The purpose of involvement is not to ask citizens which ideas they prefer, but to explore which ideas are likely to work.”

“Co-creation is hard and difficult work – sometimes even painful,” added Mr Bason, Director of MindLab, an interministerial innovation unit in Denmark. But ultimately, he argues, co-creation is a cost-effective means to ensure that new solutions really do meet users’ needs, and hit the targets in service improvements and better outcomes.

At MindLab, he has met agencies that have no interest or will to collaborate. “Here it can become almost impossible to create sound results; you can perhaps make them join the project, but you can’t force them to contribute.”

Sceptics also feel that co-creation raises unrealistic expectations from citizens. “When people allow researchers access to their homes or workplaces, or choose to spend time participating in workshops, they have legitimate expectations that this will serve a purpose. On the other hand, most citizens and business owners understand that in a political system, and especially in a democracy, there is no guarantee that just because a group of civil servants think that an idea is good, it will be judged so by top management or by politicians. It is necessary to clarify expectations, which usually is not difficult to do,” said Mr Bason.

Co-creation in Singapore

Co-creation of public services becomes more relevant in Singapore as society becomes more diverse, its needs more wide-ranging and expectations of what it means to be a citizen evolve further, said Dr Gillian Koh, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS).

The concept is not new to Singapore. For example, the neighbourhood watch scheme that started in 1997 saw resident volunteers work with the police to guard against crime in their neighbourhoods. “The police service recognised that the job is too large, so you need to mobilise people,” said Dr Koh.

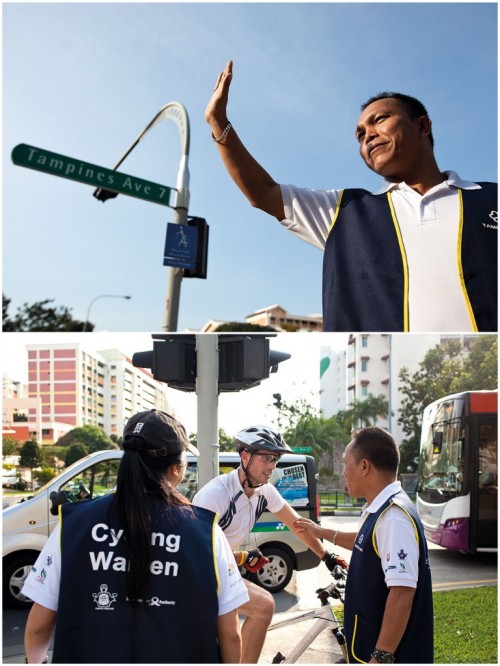

An example of a more recent public people sector collaboration is a shared footpaths initiative that started in 2007 when Ms Irene Ng, MP for Tampines GRC, mooted the idea to legalise cycling on footways in Tampines.

Cycling on footpaths is not allowed, but some residents like the elderly found cycling on roads dangerous. A pilot project chaired by Ms Ng saw the Tampines Town Council, Tampines grassroots organisations, the Land Transport Authority and the Traffic Police seek ways to share footpaths safely. Based on consultation and feedback from residents, footpaths were widened and dedicated bike lanes built.

Significantly, volunteer cycling wardens were recruited to conduct regular patrols and to educate both cyclists and pedestrians to share footways safely.

Mr Steven Yeo, the grassroots leader in charge of the cycling wardens, said: “This project shows that Singaporeans are more willing to take ownership of issues and that government agencies are more receptive, even welcoming, of our feedback.” Currently there are some 100 wardens and about 10,000 Tampines residents have benefited from volunteer-run cycling clinics. Ms Ng said: “When Tampines was designated Singapore’s first cycling town in March last year, it was a tribute to the community spirit of our residents.”

Mr Teo Ser Luck, Mayor of North East District and Senior Parliamentary Secretary, Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports, told Challenge: “This project... builds confidence and a sense of autonomy. In the future, we hope to see more Singaporeans come forward to be part of local solutions.”

The National Parks Board (NParks) is also cultivating open communication in a big way. Mr Han Jok Kwang, an avid cyclist who uses NParks’ Park Connector Network regularly, is a member of PC&Frens – an NParks initiative to keep connected with park connector users. He sends feedback on cycling paths, safety issues and suggestions for improvement such as installing a ‘fisheye’ mirror at a blind spot along a path or speed strips to make riding safer.

Another NParks example of residents taking ownership of local areas is Community in Bloom – a collaboration with Community Development Councils. Since its launch in 2005, the number of community gardens has blossomed from 100 to 400, beautifying neighbourhoods and fostering social bonding.

Mdm Kamisah Atan, an active South West District community gardener, joined her neighbourhood gardening plot in 2006 to attempt growing sunflowers, one of her favourite flowers. “The community garden gave me a chance to work as a team with my neighbours,” she said. The joy of harvesting crops of fruit and vegetables was further enhanced in 2010, when their little garden won the best Resident Committee garden award and Platinum prize in the Community-In-Bloom 2010 awards.

Tagging problems online

In New Haven, Connecticut, USA, resident Ben Berkowitz grew frustrated about his neighbourhood’s lingering graffiti problem. Numerous attempts to get city officials to clean up the neighbourhood went unheard.

A computer programmer, Berkowitz launched an online application, SeeClickFix, in March 2008 to allow residents to take a photo of a nonemergency public issue – a pothole, malfunctioning traffic light or graffiti – upload it, tag its location and send it to relevant public departments.

Many municipal governments have since adopted the application to improve responsiveness. In October 2010, SeeClickFix registered its 61,000th user-submitted issue. What sets this website apart is fostering tangible connection between residents and public agencies, reducing service redundancies and increasing active citizenry. Said Berkowitz: “We hope to get citizens participating in government rather than just consuming it.”

Potential and Pitfalls

These examples highlight a burgeoning culture of collaboration between citizens and public officers. An IPS survey in 2009 found that more Singaporeans want a greater say in policy-making, compared to 12 years ago. 85% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that ‘voting gave citizens the most meaningful way in which to tell the government how the country should be run’, up from 72% in 1998. 95% also agreed or strongly agreed that there should be ‘other channels by which citizens can express their views on government policies’, up from 79% in 1998. The proportion keen to serve on government-related bodies also doubled from 24 to 48%.

But tellingly, only 8% would actually make their views known. This signals “limited faith in the effectiveness” of the channels of engagement, said SMU’s Prof Tan.

It is not a situation isolated to Singapore. Countries with long histories of community engagement also face disjuncture between ‘wanting to participate’ and actually doing so.

For instance, a study of the City of Moreland (with a population 150,000) in Victoria, Australia, showed that “subtle power imbalances” between the community, authorities and property developers created ineffective and unequal partnerships. A major pitfall in the co-creation drive is that community engagement tends to become tokenistic and “confined within narrow parameters” such as invitations to citizens to provide responses only on specific proposals rather than opening out broad and inclusive debate.

For the Public-Private-People (3P) model that forms the basis of Singapore-style engagement, co-creation should blur the markers of what’s in the public and people sectors, said Prof Tan. “[The] 3P partnership tends to be marked by a contractual agreement spelling out the rights and duties and liabilities of each party. Once there is ‘turf-marking’, it becomes a transactionary service creation rather than genuine service co-creation.”

This and the Moreland City study show that deep changes are necessary to achieve genuine local participatory governance. It could mean changing the fundamental structures of power and communication.

Inculcating Engagement

Co-creation based on active community engagement is not something that ‘just happens’. A language or system of engagement is needed to enact the structural shifts that allow for co-creation. “A commitment to genuine engagement, respect and efficient communication relies on determination and developing personal skills to a high standard,” state the authors of the Moreland City study.

“This is hard to teach and has to be modelled through facilitators,” said Dr Koh. Most people look to ‘an authority figure’ to run discussions and raise issues. Ideally, this means to survey and assess a situation and act as a neutral sounding board to enable groups to arrive at a solution on their own. Think of it as marriage counselling or conflict resolution training, where parties slowly learn the skills to negotiate issues in an open, neutral and reciprocal way.

To do this, both the Public Service and citizens should:

- Engage constructively through channels of communication

- Improve communication and listening skills. This means learning to share and discuss information, state positions and – most importantly – listen to alternatives

- Learn to resolve conflicts of interest and viewpoints

- Define common ground, disagreements and compromises

- Allow time for parties to think about issues and reposition themselves to reach an agreed conclusion – even if it is to still “agree to disagree”

Achieving Co-creation

Are Singaporeans and the public sector ready for such wide-ranging shifts? Some fundamentals are already in place, said Dr Koh, such as an “entrenched complaining culture”. “[It] shows there is potential for a lot of citizen engagement. When people complain, it means they can see what is wrong with it; and secondly, they feel it needs to be fixed.”

Co-creation is not something that can happen overnight, or even in five years. The skills needed and the active learning/re-learning process of co-creation require patience and dedication. Citizens must come forward for constructive change; the Public Service must facilitate change in mutual collaboration and trust. Expectations must be managed; civil society must accept that not all views can be taken onboard.

That both the people and public sectors will have to negotiate new ways of talking to each other is something Mr Lui recognises.

“It will ultimately be the people and culture that determine if Gov 2.0 is going to be a success,” he said. “In this new ‘Gov-with-You’ approach, the public sector ought to embrace a collaborative culture where it accepts that some services can be more effectively developed and delivered in partnership with the private and people sectors.”

Healthcare by the People

In the UK, the Shared Lives initiative has, for 30 years, paired up disabled people with families for mutual support. In the Expert Patient Programme, in place since 2002, experienced tutors who also suffer from chronic illness educate peers on managing their chronic conditions. The National Heath Service funds the service as a social enterprise.

The scheme has benefited more than 50,000 and has helped decrease outpatient visits by 10% and visits to the Accident and Emergency unit by 16%. Meanwhile, pharmacy visits rose 18%, as patients said they feel more confident in managing their illness and were motivated to keep to their medical regimes.

As UK Prime Minister David Cameron has noted, “the public become, not the passive recipients of State services, but the active agents of their own lives. They are trusted to make the right choices for themselves and their families. They become doers, not the done-for.”

- POSTED ON

Mar 16, 2011

- TEXT BY

Sheralyn Tay

-

Deep Dive

Strengthening Singapore’s Food Security

.tmb-tmb450x250.jpg)